An Interview with Federica Foglia

I began exchanging emails with Italian filmmaker Federica Foglia in June 2022. Having just finished watching Autoritratto all’Inferno (Selfportrait in Hell, 2021), I was enthralled by the fragility and sensitivity she conveyed on celluloid. “Cinema you can touch,” someone in the theater said, and indeed, Foglia’s cinema belongs to that film realm of cornea-becoming-fingertip, like a braille text waiting to be discovered.

This led to a back-and-forth of communications by email and videocalls over three years. The final result is part of an initial interest that grew into unfathomable curiosity, but also part of Foglia’s growth as an artist. Life helped us to revisit our beliefs about cinema, and patiently we constructed this text, which is a palimpsest of ideas and feelings marked by the passage of time—a somewhat whimsical analogy very relevant to Foglia’s own creative process in working with found footage.

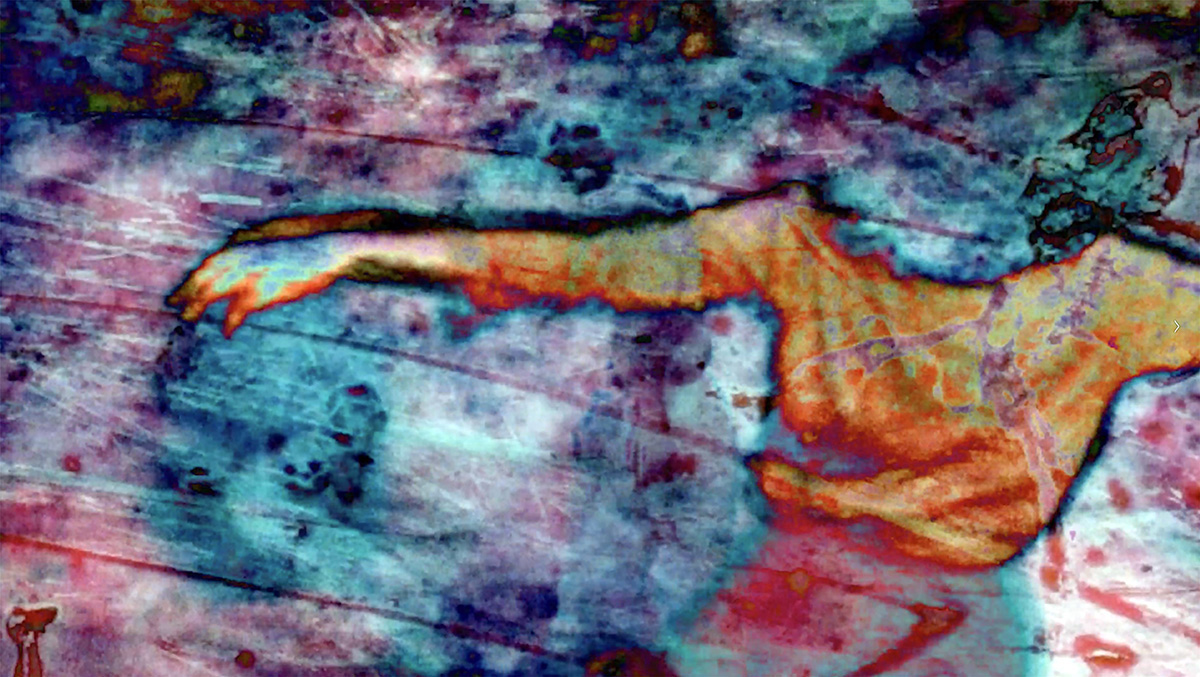

Through collage, grafting, decoupage, and détournement, Foglia’s films function as palimpsests where delicate fragments of memory are settled in layers of meaning. Living simultaneously in the past and the present, inside and outside, being and not being: diaspora and opacity (Fantassút/Rain on the Borders, 2016); the universes we inhabit and the ways we inhabit them (Currents/Perpendicolare Avanti, 2021); architecture, gentrification, the Benjaminian Umwelt where affections come from our own environment (Skyscraper Film, 2023); sexuality, agency, nature (Film Negativo/Positivo, 2023) as well as its opposite (Film Positivo/Negativo, 2023); and Foglia’s latest film to date, Glitter for Girls (2024), a playful prank that uses water tattoos for children. The palimpsest, it seems, also allows for a childlike gaze.

This interview is divided into three parts and spans the gamut of three years; hence, nearly nine thousand words that fall short of describing the breadth of this tangible text—ultimately, a manuscript/manifesto that invites the eye (and fingertips) to inhabit the cosmos that is Federica Foglia’s filmography.

Lima, Toronto, Milan

Part I · June 2022

José Sarmiento Hinojosa: The first question I wanted to ask regards your evolution as a filmmaker. You started your career in documentary, then progressed into experimental filmmaking, and now you’re working with archive material. How do you see this process in retrospect? How and when did you start making films and when did you decide to work with found footage?

Federica Foglia: I moved to Canada from Italy nine years ago and approached filmmaking in parallel with the beginning of my immigration process. As I moved between countries, something shifted inside me.

I started making films for that reason, to process some sort of displacement. I stumbled upon documentary in 2016. I was stuck in Canada, waiting for my permanent residency visa. It was a very long immigration process; I was not allowed to work until the visa approval. Around that time there was a peak in the immigrant crisis in Greece (Lesbos), lots of pictures of refugee children, bodies washed ashore. These horror images were pouring constantly from media around us. It really affected me, I felt shattered. I looked for weeks at images of immigrants at European borders, stuck in a limbo.

This was another form of displacement that was affecting these people. Of course it was not the same as mine, I was an immigrant with agency who voluntarily decided to go to another country—while they were fleeting from death. I needed to do something about it. I didn’t want to be a passive witness. So, I went to volunteer in Idomeni at the core of the European refugee crisis. I had my DSLR camera with me, though filming was not in the plans. During the last three days of my volunteer shifts I felt that I needed to bring back a witness account of what was happening in the camps—through the voices of those who were affected. So I started filming interviews, truly a documentation of the facts that my eyes struggled to believe. I wanted to be there and I wanted to see, and then I wanted others to see what I saw and activate some sort of response. As I was there, I kept reflecting on many things: how their story is so different, how it is similar in some aspects, how these big movements of people are reshaping both physical and emotional geographies. Everybody’s shifting around in the world for several reasons: war, the economy, climate crisis…I’m really interested in the shift of people in the world. That’s how I started.

Then I moved towards experimental cinema. In Canada I started filming with a Bolex. I was filming my surroundings, and it didn’t look good. Even though technically everything was perfect, it didn’t feel authentic to me: you are in a place that is not your home, and it has a big history of colonization as well. I’m from Europe, and I come to Canada with a settler heritage. How can I film it authentically? It’s not possible. It’s not true. It doesn’t belong to me. I don’t belong to the country yet. I need to find out how to create images of this place without mis-visualizing it or misrepresenting it. In fact, I don’t want to capture images of it at all. The idea of capturing Canada with my lens is very problematic for me.

I started looking for old documentaries about archival material and stuff like that. The questions in mind: how are people from Canada filming the place, and why is my perspective so different? How can they film these beautiful orange colors in the woods, or the texture of the snow? I could never film the snow here. It’s very hard.

I got 16mm archival footage and started working with it. And that’s how I fell in love with found footage. It was a very eye-opening experience. Because I felt that I could make a story of my own by borrowing someone else’s material (with all the ethical implications that this entails). That opened a lot of mental doors for me, on the concept of authorship and being able to create something out of footage another person had shot. Recycling visuals and sounds.

I don’t have the urgency to shoot my own original material. I’m okay with recycling materials of others and I hope others are okay with me recycling their materials. I try to be respectful in my re-assemblage and re-montage.

J.S.H.: There’s this diasporic experience that is present throughout your work, from your first documentary to Currents/Perpendicolare Avanti. Do you still feel like today you’re living a complicated moment in your life? Being from Italy and being now an expat in Canada, how does that spill over into your work?

F.F.: I don’t think it’s complicated in the sense that I’m not living a traumatic displacement. I moved voluntarily. For me, it’s very strange to be in two places at the same time, because I stay very anchored back to Italy. Every day I have constant communication there, and at the same time, I live here. It’s an in-between space. At the beginning, you feel like you’re fading away from the country you belong to and you’re starting to merge with a new country, trying to navigate your sense of belonging. At the end of the day, you realize you belong in both places at the same time. I think this experience is the same for many people who move between countries, the acceptance of this double split.

For me this sense of a split identity is something you never get over.

J.S.H.: You have a very clear idea of what you are doing. I read your MFA thesis and also watched your video essay on your practice (https://www.federicafoglia.net/videoe-say-my-practice) and found some clear concepts. For example, you talk about affection a lot—the exercise of affection. You use a Walter Benjamin term, which is Umwelt,1 and another word as well, Frantumaglia.2 Do you think we can talk a little bit about that?

F.F.: Frantumaglia in Italian is a word that I borrowed from a book by the very popular writer Elena Ferrante—the novel is set in Naples, which is my birthplace. It was the only book of hers that had been translated here in Canada. While reading Ferrante, I found this concept in her book: “The state of mind you find yourself in when things seem to dissolve around you—even visually.”: things and borders, the borders of the objects and your surroundings are a bit dissolved, and they merge into one another. That’s something similar to what I do with my films. They are made from a lot of fragments glued together with no real contour.

This is also true of life in general. I don’t think we are isolated bubbles. That’s why the concept of Umwelt comes in as well. We don’t live in our own environment in isolation. We are constantly affected by the environment, by objects, by politics. Even the films that I buy—you know, I get these old films in dusty cans, sometimes from eBay. I don’t know who they belong to. Some are from the 1940s; they are abandoned, orphaned films. And when I take them in my hand, physically, they affect me somehow. It’s an object, but it has a certain power. It’s charged with power.

I’m searching for a way to be organic in the world that surrounds me. And this negotiation comes through materiality and aesthetics

The concept of dissolved borders returns. You touch these celluloid strips and you feel that the material merges with your own DNA, and vice versa. Where is the border between me and the film emulsion? And how will these old images contained within the found frames affect the images in my head, and vice versa?

I’m searching for a way to be organic in the world that surrounds me. And this negotiation comes through materiality and aesthetics. My interaction with the world and with film and with the objects and with the country is mediated through the material, through the performative and tactile experience. It cannot be mediated with intellect because this is not an intellectual process. This is a visceral process. Especially when you’re in a new country, you’re like a child again; re-learning a new life, a new language, your experienced reality becomes pre-verbal.

Maybe my body is helping me orient myself in this world of double belonging. This is where I am now.

J.S.H.: You’ve spoken about the tactile element of your films. I think it’s very interesting because there are echoes of that even in L’arrière-pays (2020), an early experimental fiction short. I find this element of intangibility, the not being able to properly touch each other. It was quite fascinating to watch how early this concept was echoed what did came next, what you made after that through different elements of filmmaking, then “translated to the physical material of celluloid” of the celluloid.

How did you discover this process? Because you now work with the emulsion of film. You’ve developed this method where you just strip away this very delicate layer of emulsion, and then you transpose it to another strip of celluloid. The effect is outstanding.

F.F.: What you say about “not being able to properly touch each other” makes a lot of sense, and in a way my films are an attempt to overcome this—to be able to interact with others in the most authentic and clearest way possible. Bizarre that all this clarity I look for lies between broken/collaged/distorted fragments of sound and images, and ultimately in their montage.

I arrived at the technical aspect while I was studying with Phil Hoffman, the experimental filmmaker—a mentor of mine. I was taking his Process Cinema class. I had never worked with celluloid before. He introduced us to phytograms. This process, developed by Karel Doing, involves placing some flowers previously soaked in a bath of vitamin C and washing soda on the filmstrip in direct sunlight. That was my first proper experience with celluloid, affecting the emulsion layer with the internal chemistry of flowers. It was mind-blowing. Absolutely beautiful to see almost an x-ray of the plant’s innermost structures on film.

I spent the whole summer doing phytograms. We were in full lockdown (Covid) and there was nothing to do. I was making these phytograms in the garden, which was a tangible experience. It’s like, there’s a virus that is immaterial and invisible, that is around you, and you need something material to ground yourself. So, celluloid came in at that point.

From there, I just started to get more and more interested in 16mm film: celluloid, the emulsion layers, the base, and all the colors, one on top of the other—if it’s color film. That materiality for me was crucial at a moment when everything was immaterial. Remember, we were on Zoom all the time, talking to people only virtually, attending classes virtually, not going out of our houses. The material for me at that moment was an anchor.

In that phase everything came together. What I had learned about the chemical qualities of the filmstrip and its components, I then applied to the found footage I had amassed over the months. Then I landed on emulsion lifting. Cécile Fontaine discovered this technique3; she’s a French filmmaker still practicing. I think in the 1980s was the first time that she stumbled upon the technique. She was working with ammonia and tape, and she realized that the layers of emulsion would peel away easily if processed with this technique.

By that time, I was really focused on messing up 35mm film slides that I found in an auction with the bleach powder that I use for my hair, peeling away the several layers of emulsion. I made some films out of it, [including] a 16mm film that was really hard to scan. I took it to a lab here in Toronto (Frame Discreet). After that, I started to get deeper into understanding what happens to the emulsion when attacked in all possible ways.

Is it possible to peel it off, leaving the images intact and transferring it somewhere else? And why am I doing this? This is clearly a metaphor of my immigration process, right? I’m lifting my story up from one place and transferring it to another, merging several stories together and then rewriting everything in the montage. The filmstrip became my life, made of many fragments.

This process is guided by the gestures of the hands, but it makes you see things, it’s very powerful mentally. It makes you think about things with your hands, not with your brain. You acquire knowledge about yourself through your hands, knowledge about your surroundings through your hands. It’s a different way of orienting yourself in the world, as we said before. And it’s also a very delicate process of push and pull and caresses.

J.S.H.: I was watching the video you sent me on your process, and it’s indeed very delicate. Whatever you do, the lifted film emulsion can easily break apart.

F.F.: It depends on the film stock that you use. For instance, today I was working on this black-and-white film stock from the 1940s. To peel the emulsion off this one, it was a nightmare. It was so fragile. The images dissolved completely, and I was left with some fragments of blacks and greys.

Now this [shows it to the camera] is a different kind of technique that I’m doing. It’s still emulsion lifting, but compared to what I was doing before, it’s an evolution. Before, I was stripping the emulsion off the film base, then as it was wet in my hands, I placed it onto another filmstrip. What I’m doing now after stripping it away is placing it onto these big canvases and letting it rest there until the emulsion is dry. Once it completely dries out, I can pick it with a tweezer and assemble it more in a collage way, like in Skyscraper Film. This workflow allows me to make more intricate collages, because you can take just a little tiny piece of this dried emulsion and put it on the other strip. I think Cécile Fontaine does something in a similar vein with her dry lifting technique vs wet lifting (although in the dry lifting technique she deploys tape).

The wet lifting technique I was using before was more immediate; I had to improvise a lot. I peeled the emulsion off, then, wet as it was, I had to put it on another strip immediately. Now I’m buying myself more time for collaging. Before it was more instinctive, and you could combine a maximum of two or three celluloid pieces, because it’s wet and it slips and it’s really hard to put too many layers on top of each other. With this new approach, because the lifted film emulsion dries, you have these big sheets of fragments and so many options. There are five different films on these sheets. You can just say, “I want a piece of red, and then I want a piece of blue, and then I want this skyscraper in black-and-white”. You can just go wild.

J.S.H.: There’s a very beautiful metaphor hidden in this process, like you said. Working on the displacement of the image, it’s like transferring your whole experience of traveling to another country and also the experiences of other diasporas and other migrants. You do the same with the image. You’re just trying to carry it to a new place.

F.F.: Phil Hoffman, in one of our conversations, said it very well: “I think you’re working this way because what you see around you doesn’t feel real to you.” So, what I’m trying to re-create on these filmstrips is what my world is. All these fragments that move around, this is how I perceive the world right now. I must visually represent it this way because it’s the only way that feels authentic to me.

J.S.H.: Yeah. I think it ties very well with another term that you have used, and I think it works beautifully, that it’s like the queerness of not only your own self, but the queerness of the reality you are experiencing as well.

F.F.: Because I don’t think there are straight lines, straight edges, straight definitions. Édouard Glissant and the concept of opacity: that was a concept that was with me at the beginning of this discovering. Things are opaque, things are not clear, and these are visions that emerge and you cannot intellectualize them all the time to make sense of them. You must just sit there and absorb these visions and see where they take you. It’s just a puzzle that I’m trying to compose. And then, at the end of it, we’ll see what it was.

J.S.H.: Talking about puzzles, there’s something I want to recompose in my mind: in Toad, Leaf, Grass, Rock (2020), there’s an image that burns out at the end. Then you made Self-portrait in Hell, with an image of a woman in hell, which felt like a continuation on that subject. Later, in Skyscraper Film, there is also a descent into a circle of hell, like a metaphor for Dante’s Inferno, taking architecture as an element. Is that something that occupies your mind?

F.F.: For me, the concept of hell has a lot to do with struggling to grapple with one’s own mind and internal world, when they are not crystal-clear, when you don’t understand or recognize your own self or are even at the mercy of your own self. You’re trying to make sense of it. Regarding Self-portrait in Hell, you are right, it’s almost like Dante’s Inferno (I’m Italian, and so it’s a very present metaphor in my mind). I call it hell, and it’s a very strong word to use. But I try to make this hell a comfortable place for me. In that film, you see this woman dancing in this hell, surrounded by all these beautiful colors and fragmentations. Yeah, it’s beautiful. It’s disturbing.

We all go through some sort of hell in our life at some point, either collectively or personally. And we have to try to make this hell a very comfortable place for us, because we might be there for quite a while and we must make it our environment. When life gives you lemons, you make lemonade. So, when life gives me mental health problems, I make experimental films. Yeah, that’s my philosophy.

J.S.H.: (Laughs) Sorry. No, it’s okay. That’s so funny.

F.F.: Yeah, okay. That’s a great analogy. That’s what I do.

Well, it’s beautiful. That was my hell. And then in Skyscraper Film, there’s a total fragmentation happening around me, and it’s a different kind of hell. In that case, it’s not a personal hell. This is a film that comes from my way of dealing with the surroundings and the spaces of North America, spaces that are invaded by a lot of architecture, skyscrapers, and tall buildings. In Italy, there are not very many skyscrapers, so this is another way of re-assembling my surroundings. I hate all this glass. I hate all this concrete. I want to break it down and tear it apart and make something nice out of it. In a sense, trusting the power of aesthetic intervention to do the thing that can’t be physically done singlehandedly. I have great faith in the power of aesthetic intervention.

I also love the idea of working with something that originally was not intended for this purpose. The films I’m using are institutional films commissioned by the government to sell you a nice idea of different cities in Canada. One is called Bonjour, Quebec. It sells tourists on how beautiful Quebec is, the skyscrapers and the buildings. I’m using material that is meant to lure you into the beauty of North America, to say: for me, it’s not like that. It’s very troubling.

I live in Toronto. Since I arrived here nine years ago, there are big skyscrapers being built on the lakefront every week. This beautiful lake, one of the biggest lakes of Canada, is screened from us. There’s a wall of skyscrapers. They are obstructing the lake from people with all these big buildings. And random people from abroad that have a lot of money buy the buildings and rent them out. It is gentrification magnified.

J.S.H.: There’s something that captured my attention in your master’s thesis. You’re talking about Italo Calvino’s Le città invisibili and the invisible cities. And you’re talking about the dreamlike, shifting nature of memory. Do you think you can expand on that? How does that relate to Skyscraper Film in particular?

F.F.: I read that book when I was young in Italy, and it stayed with me. And I found echoes from that book in L’Arrière-pays by Yves Bonnefoy, which is a title I reused for another film I made. These two books were written at the same time, almost in the same year, by these two writers in Paris. Both share this concept of the immateriality of cities, the concept of a city as an interior city, not a physical city. It’s not geographical. It’s a city made of fragments, of memories. A city made up in the mind of the city. This concept differs a little bit from Calvino to Bonnefoy.

For me the possibility of a city that is not there was very important. Bonnefoy and Calvino share a very similar concept of a city merging mentally with another one. In both books, you travel from one city to another in a very organic way. Concisely, in the Bonnefoy book you are reading about the city and then there is a jump cut and you’re transported into another one, and you suddenly don’t know where you are. That resonated a lot with my experience here in Canada. But I think it is not solely about memory/memories—for me it is also about building imaginary possible futures. There is a lot of nostalgia and attention to memories especially in art that deals with diasporic/migrant experiences, or even in the discourse around the archives.

Part II · April 2023

J.S.H.: Let’s go back to Skyscraper Film. The idea of architecture plays a pivotal role in the form of articulating your film material structurally. How do you develop the idea of the architecture of film in accordance with the architecture of buildings?

F.F.: Skyscraper Film was triggered by a series of conversations, readings, and exchanges around the relationships between space and cinema. In this film I confronted the architectural spaces of North America. The space around me and its architecture have always felt visually hostile to me and inappropriate for human well-being. We spoke about this before, but the lakeshore in Toronto has slowly turned into an eco-disaster of constant condo development and building, blocking the city from the water. Taking a stroll or a drive through the city, you are overwhelmed by the number of concrete construction sites, similar to many other cities that I’ve visited in North America. I started collecting found footage reels and archival films that reproduced images of these skylines, buildings, skyscrapers, and so on, and decided to use them visually to attempt to melt them away, to give free reign to my desire for demolition.

As I was cutting and selecting the scraps to use in my future collage, I couldn’t help noticing the orderliness and geometry and solid lines of all these buildings and architecture. Everything was a schema of lines, grids, and perfect artificial shapes, so I decided to go against that and create a counter-architectural film that follows none of those structural elements of straight lines and frames, but instead is constructed around curves, cracks, and broken fragments that miraculously remain in balance on top of other broken fragments. A tearing apart of the man-made city leaves space for a more natural visual city. I remember a quote by Peter Greenaway in a video interview about his film Drowning by Numbers (1988): “…most of cinema is about the frame and you know the frame doesn’t exist in nature. As I sit here now and I look at you and you look at me, you are certainly not in a frame and you will never be in a frame, and there is no such thing in nature. By the same token, I don’t think there’s such a thing as a narrative. These are comfort zone phenomena that we put together for our convenience.” Toronto was fully framed by an infinity of man-made frames/skyscrapers.

I started collecting found footage reels and archival films that reproduced images of these skylines, buildings, skyscrapers, and so on, and decided to use them visually to attempt to melt them away, to give free reign to my desire for demolition

The lake, the sky, the trees and the land were trapped between these vertical lines and frames… I wanted to deprive the city of its frames, and by extension my film with its frame-like structure, and go outside the frames by returning the cityscape to its natural state. Often the collaged material ends up on the sprocket holes, extending outside the filmstrip. The solid lines melted into natural sensuous curves, and the skyscrapers melted away. I also injected the greyness of the skyscrapers with primary colors found mainly in nature: red, blue, green, and yellow, following the same principle. Ultimately these old 16mm film scraps offered themselves as a fruitful platform and tool for an architectural criticism of the urban landscape I inhabit—via an aesthetic and materialist approach.

J.S.H.: Innesti Neri e Bianchi (2023) is one of your finest works to date. You keep working with archival footage and your emulsion process in a constant evolution that finds new ways of working with the primal material of cinema. Can you tell us a little more about how your process with emulsion cinema and the archive has evolved in this work?

F.F.: When it comes to found footage and the orphan films that I work with, theoretically the approach remains the same, but technically it evolves. For Innesti I tried for the first time to incorporate analog and handmade film manipulation with digital manipulation, so you will see a series of disparate analog techniques such as emulsion lifting, film decay with soil, water, paint on film, and scratching, alongside all sorts of video transitions achieved through editing software. For years I was trying to do everything manually, and I am still very much in that mindset, but I didn’t want to become a dogmatic artist. It was nice for me to break out of that self-imposed all-analog manipulation.

For Skyscraper Film, I tried yet another approach to emulsion lifting. I usually work with this technique in its wet form, meaning molding the material/the celluloid when it’s still wet and looks more or less like a blob. The material in that form is very fragile, slippery, and elastic. But this time, I used an emulsion lifting approach with dry material. With this approach the emulsion is lifted from the film base—as would happen in the wet emulsion lifting—but this time it is not wet. It appears in the form of small celluloid fragments detached from the polyester base, almost like the crêpe paper we used as children in kindergarten. In Italian, it was called carta velina, which I think translates to “colored tissue paper.” The material you work with is ethereal but dry. With dry emulsion lifting, everything is easier; the assembly of the film scraps through that technique can be very precise and made up of minuscule fragments, a thing that is not quite possible with wet celluloid.

As I continued to work on this technique and became more familiar with all the steps involved, I realized that the term “emulsion lifting” lacked something. Certainly, the process is one of “lifting” the gelatine emulsion from its original film base, but then the lifted emulsion gets grafted onto another film base and onto another image. I see this process as very similar to plant grafting. What is a graft? Encyclopedia Britannica defines it as follows: “in horticulture, the joining together of plant parts by means of tissue regeneration. Grafting is the act of placing a portion of one plant (bud or scion) into or on a stem, root, or branch of another (stock) in such a way that a union will be formed and the partners will continue to grow.”

As a result, I started referring to my process as emulsion grafting, a term that incorporates both the action of lifting/cutting and the final step of gluing, [thus] making images initially not belonging to the same filmstrip adhere and become one “…in such a way that a union will be formed and the partners will continue to grow.” Bringing together images that don’t belong to each other, or to the same narrative, is a visual metaphor of myself trying to bring together the two parts of my life and identity: Europe and North America. It’s a visual representation of my integration process as an immigrant.

Part III · August 2024

J.S.H.: I’ve been watching your last two films, and I first want to talk about Film Negativo/Positivo. It seems, at first glance, to deal with a sense of discovery about identity, queerness, and the erotic. There are images of a caterpillar on a butterfly, and there’s the image of the female body and the merging between this creature that you make on your collage, which is part butterfly, part woman. I understand that maybe saying this can feel a little bit reductive, but I wanted to explore your ideas behind this concept.

F.F.: This film is open to many interpretations, as are all my films, you know.

With this film, it was a bit more of my subconscious coming together through my hands on the filmstrip and through these images that I borrowed. The initial idea was to—as the title Film Negativo/Positivo says—use both negative and positive film stock, black-and-white, both on the same filmstrip. So that was the technical aspect of it. I wanted to see what happens when you combine negative black-and-white and positive black-and-white on the same filmstrip, and then reverse it afterwards. So, there are two versions of this film, really. The second version I haven’t shown yet; Film Positivo/Negativo looks quite different from the first version. It exists also in the shape of an installation.

At the same time, I was fascinated with the idea of working with bodies of women and flowers, plants, and natural elements intersecting with the human body. When I started making this film I was concerned about (still am) the environmental crisis that we are creating. But it wasn’t intentional. I had this desire to merge natural elements and the bodies of these women and use those merged elements almost as a decorative motif. For that, I needed a lot of white space on which to overlay the pattern of the flowers and nature. And what gives you a lot of white space is the naked body—in my case, naked bodies of women.

I started looking for erotic black-and-white films. There were amazing orphan films, black-and-white, floating around in the world that I grabbed. Spontaneously in a very instinctive way, I started cutting male bodies out of the picture because I wanted to carve out only the female bodies. As I was doing this, I realized there was much more behind that gesture. It wasn’t just something I was doing for the technique or for the material or for the image itself or the final visuals I wanted to achieve. There was something that was coming from within me through those gestures.

I was carving away these images of men. And then I was giving prominence to the body of these women. And I was visually multiplying the women. As I was going through this, I started grappling with the possible meaning of the film coming full circle with myself, acknowledging myself as a complete, unique being that doesn’t want to rely upon a potential male partner or a potential female partner. In fact, if you look at the two women interacting in the film, you see that they are the same woman. It was a way to legitimate myself in my own complete being. When the two women are kissing each other, it was this personal embrace and personal reminder that we as human beings are self-sufficient for our own existence, hopefully in harmony with nature and the environment around us. I see myself in harmony with and in the same realm as the caterpillar, the butterfly, the leaf, the grass, the flower.

I wanted to send a prominent visual aesthetic message about the importance of us merging with nature in a very respectful way, to emphasize that we depend upon each other and there is no hierarchy here. At the end of the film, there is this woman, she becomes almost imbibed in the flower garden, and then there’s a metamorphosis into a moth.

J.S.H.: This underscores the significance of working with found footage. The process of resignifying images is inexhaustible. It seems that you have opened a channel to your unconscious, allowing it to permeate your filmmaking process—an act filled with meaning. What’s fascinating is that the film resists closure; it remains in flux, always appearing as a work in progress.

F.F.: Even my own interpretation of found footage has changed over the years. Initially, I thought that it had to do with my immigration process. It had to do with the fact that I was displaced in another country and I didn’t know how to orient myself. So, the images of others came to help me ground myself in the place where I was. I started working with found footage of Canada and so on.

But the more I think about it and the more I move myself through the world and through several experiences, I have been noticing that I turn to found footage each time I am unsure about myself, my identity and my place in the world.

You aid yourself with images of others that are more tangible in a way than what you feel yourself in that moment. They come to support you in moments of bereavement. When I was a newcomer to Canada, everything felt vague and felt too slippery and intangible. Then found footage becomes that tangible material because, first of all, it doesn’t come from you. It doesn’t come from the uncertainty of what you’re feeling, rather it comes from something certain outside of you. Found footage is that safety ground out there that comes to you when you are living through unsettled times (whether external or internal).

I’ve noticed this with other filmmakers, too, that I have become familiar with through my process and through my research. Names like Frédérique Devaux come to mind. She said it beautifully in an interview where she mentioned that she doesn’t feel either French nor Algerian, and her use of found footage stems from the fact that maybe she also felt like a foundling—she does amazing work with found footage. Another example is Cécile Fontaine, who used to work in France with the footage her father sent her from La Réunion.4 Also, a lot of indigenous filmmakers are working with found footage, like Christina Battle in Buffalo Lifts (2004). Or think about how Brakhage attacks celluloid; I only recently discovered he was adopted and that was not his real name.

I’m not saying all these artists have the same kind of identity issues, but I’ve definitely noticed that material intervention on celluloid or found footage serves as a solid departure point in moments where identities are uncertain or questioned or threatened.

J.S.H.: I completely agree with that. And I think filmmakers like yourself and others are inscribing themselves into this history that began before cinema was a thing, with the use of archival material. I think about the war journals of Bertolt Brecht,5 where he used to do collages about the war, in exile. There’s a whole book by Didi-Huberman that deals with that.6

Appropriating other people’s images to find a sense of identity or place in the world is something that has been done in art history for a long time now. And I think it’s fascinating how it continues to serve as an unlimited resource of meaning.

F.F.: You recognize yourself in that image that preceded you. And you see a gesture, or you see a look, or you see something in that image that in that moment sparks a light within yourself and makes you see yourself in that. It covers a ground that you had not seen with your own eyes before. It’s an aid. It’s an aid from the outside, at least for me.

I’m so grateful to found footage because there’s an excitement between every new image that you find. And when you unload the film reel and start seeing what’s in there, and then you wait for the message, you wait for that moment of departure. You are not just working with found footage, you’re re-animating emotional residues stored in images of others.

With Film Negativo/Positivo, as I said, it was about reconciling all sides of me. I can tell you about this only now that some time has passed. I wasn’t completely aware of this, but it was an exercise of reconciliation within myself, within all my sides, and within nature as well, in a bigger scheme. This is a film like a Russian doll. It’s multilayered. It’s probably the most multilayered film I’ve ever made in terms of meaning, and I love that because everybody can see parts of their own experience in it.

J.S.H.: There’s also Glitter for Girls. It can be seen, I think, as a cute girly film in the whole aesthetic of it, even the sound choices you made. But I think it goes way beyond that. There’s a projection of a playful childhood with this method of crafting a collage with…is it water tattoos that you use?

F.F.: Yeah, it’s the tattoos, I don’t know if you had those in Peru, but in Italy we got them when you bought a bag of chips. And you would put them on your skin with water. You’d just wet them and get the tattoo and you’re cool, you know? That’s a very childlike thing to do I think that capacity of letting your inner child be surprised by the little elements of life is very much alive in the film.

J.S.H.: It’s a sense of wonder and a sense of magic, like a magical experience. You can reminisce about earlier times when life was simpler, maybe. Can we talk a little more about what went through your head while making Glitter for Girls?

F.F.: That film started from a material experiment—when I lift film emulsion I work with something that has a consistency similar to the gelatinous skin of milk, the thin and fragile veil that is created when you boil milk. It might also be felt when your own skin peels off after taking too much sun. Aside from that feeling, the lifted film emulsion is very thin and transparent, allowing light to shine through it. Temporary water-tattoos incorporated all these qualities (lightness, fragility, colorful transparencies) plus another: they would stick to the film base similarly to film emulsion. But the reason why I think I picked water tattoos (I could have picked any other thing that had similar qualities: butterfly wings, a Letraset kit, and so on) is because with over the years I started sensing more and more the affinity between my own skin and the skin of the film. Sculpting away on the film surface—often with wet hands—and noticing how my fingertips and the film emulsion would show similar cracks.

One day I found these little water tattoos in the house, which I had purchased years ago; then I found other tattoo sheets outside my house a week after, so I said, oh my God, this can work because if it sticks to my skin, it’s going to stick to the film surface.

It was such a fun experiment. And that’s [an important] part of it, the playfulness you were talking about, because especially when you’re a woman filmmaker, you feel some sort of pressure to deliver work that has a deep meaning. I felt that I was not letting the playful part of my craft come through. I just wanted to make a film. I’m allowing myself to make something meaningless in a way. But in a sense, it has a lot of meaning because it’s about the liberation from these clichés, and it’s about pure images and sound and movement. And who says that’s not a deep subject? The aesthetic of the film itself, the animation. I worked a lot with animation techniques in this one that I had not used before. I tried to animate stars. I was also influenced by a show by Robert Lepage on the life of Norman McLaren.

J.S.H.: When Glitter for Girls ends, you can see the film in its material form. You show the lightbox at the end of the movie, which is a testimony to this huge process of making the film. The lightbox itself, are you planning to exhibit it?

F.F.: I exhibited in Pesaro, at the Mostra del Nuovo Cinema di Pesaro last year. They had a little retrospective of my films curated by Mauro Santini, Fulvio Baglivi, and Roberto Turigliatto (From the Rai 3 program Fuori orario). And I sent this tableau with all the materials that are tangible and visible. We’re talking about material cinema. It helps everybody if they get to see and touch what it’s made of. These are real filmstrips. I have noticed that people, most of the time, don’t realize how it’s done. This kind of cinema needs context sometimes, and I guess these artifacts really help.

J.S.H.: Let’s talk about the sound of your films, especially in Film Negativo/Positivo and Giltter for Girls. Can you talk about the process that you went through to construct the soundscapes? It seems to be made of different sound bites and compositions.

F.F.: This is the same process I use for all my films. If I am collaging images, the spirit is the same when it comes to music. I like to work with found sound.

Sound and images exist on the same plane, and they have the same power for me. My movie would not exist without that kind of collaged sound. Sometimes my editing follows the collaged sound that I find; the pace and the editing and the transitions that you see in the film are (quite often) dictated by the sounds that I assemble.

I find the sounds on several free websites. I haven’t worked with anybody on my own films because the process is so personal; it’d be the same thing as asking someone to lift the emulsion on my pieces for me, or edit for me, or select the found footage for me. That’s the whole fun of it. I’m having so much fun assembling those sounds. Why would I give it to somebody else? It also helps you have full control of all these elements, because the work is so open and so fluid that sometimes the story will come through on the editing timeline. Maybe I have in mind a movie of five minutes. I end up with a movie of twelve [minutes] because the sound that I found transported me to such a space that I need to go back to the footage and pull more collage to fit in that part. The sound is not necessarily subservient to the image. Sometimes the images are subservient to the sound too. There is no hegemony of image or sound for me. Possibly both are at the mercy of the montage.

J.S.H.: Since we last spoke, I believe your methods on camera-less filmmaking have progressed a lot. Can you guide us through this transition of what is new and what you kept from your original methods and how it has changed?

F.F.: It comes from that awareness of the environment. I’m recycling old images, so there’s already a big component of eco-sustainability, because you are not producing more materials—you’re recycling what you get. Also, I have eliminated any toxic or chemical material from my practice. I don’t use bleach, ammonia or other stuff to carry on my process. Then I thought: is there a way of creating films on a foundation that is not plastic? There was so much polyester and plastic floating in my studio. Is there a way I can replace all this with something different? I researched and discovered some photographic experiments made with biodegradable plastics and started making my own biodegradable plastic at home, and then I rendered it photosensitive.

I think that artists are supposed to come up with ideas for possible solutions that can then be taken further by those who have the industrial means for doing such things

Then I found ways to print the found footage on it in the shape of 35mm strips. It’s a work in progress, because it’s a big experiment. These 35mm prototype filmstrips cannot be projected yet, they can only be scanned and then animated via computer. You’re sacrificing the projection for the scanning, but it’s a much more ecological way of making films. It’s a painstaking process. You are saving the environment but killing yourself as a result; I don’t know how viable this is for the future. But it’s an idea. I think that artists are supposed to come up with ideas for possible solutions that can then be taken further by those who have the industrial means for doing such things.

I’m getting more committed to an environmental-friendly kind of cinema. But I’m also interested in the material aspect of it, because these organic bioplastics, they are really open to accidents. They create patterns and opacities that otherwise you wouldn’t have with other industrially produced materials, such as polyester. It’s a little bit like hand-processing your film, you know? Literally hand-making your film, because I’m baking and cooking all of this in my kitchen. But it’s a long process, and I don’t know if I’m going to survive it. It’s a work of love, and ultimately it’s the most authentic side of me, that one fragment of truth that I keep searching for between the cracks of all these broken film frames.

Endnotes

- 1. The German word for environment, to denote an organism’s unique sensory world.

- 2. Frantumaglia (a Neapolitan word for “a jumble of fragments”) is a non-fiction book written by Italian author Elena Ferrante. The book reflects on her writing process over twenty years.

- 3. “Cecile Fontaine (b. 1957, Paris) is credited with ‘inventing’ the emulsion lift technique. She accidentally discovered the technique at a job during her college years in the United States. She used the wrong substance to clean some Super 8 film, and noticed that the 3 layers of emulsion were separating from each other […] Some examples showing the limitless possibilities of her technique are a Color Movie (Super 8, 1983), and Overeating (16mm, 1984)”. Leah Bosworth, ‘Film Alchemy: Interviews with Direct-On-Film Animators,’ Milne Library Faculty/Staff Works 2, 1994.

- 4. Île de la Réunion in the Indian Ocean. Part of France.

- 5. B. Brecht, Bertolt Brecht: Journals, 1934-55, London: Methuen Publishing Ltd., 1993.

- 6. Georges Didi-Huberman, The Eye of History: When Images Take Positions, Toronto, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2008.