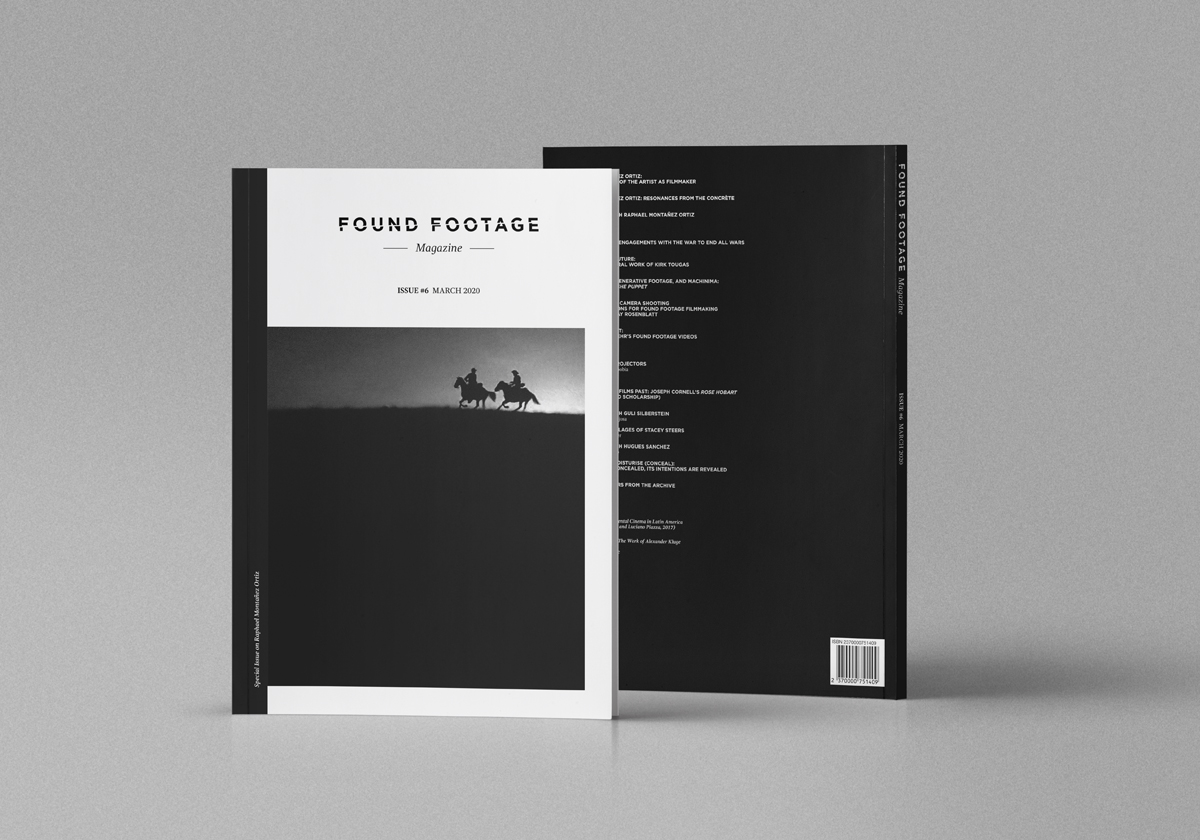

Issue #6

Special on Raphael Montañez Ortiz

+ Other contents

- March 2020

- ISSN: 2462-2885

- Full-color magazine

- English

An Archaeology of the Artist as Filmmaker, by Chon A. Noriega

In the early 1960s, Raphael Montañez Ortiz was among the first to name a new approach to the art then emerging out of a number of movements in the Americas, Asia, and Europe, movements that rejected both abstraction and traditional forms in favor of the realism of appropriating images and objects from consumer, media, and industrial culture. This approach blurred the boundaries between object and image, as well as between public and private, while it privileged the recycling, transformation, and even destruction of the material sources. Ortiz identified this emerging work in two ways: first, by pointing to a decisive and worldwide turn toward destruction in artistic practice in his ‘Destructivism: A Manifesto’ (1962); and second, in naming his own mixed media works as Archaeological Finds (1961-64). In a 1965 essay largely focused on artists associated with nouveau réalisme as well as Tetsumi Kudo (Japan, 1935-1990), French critic Alain Jouffroy called attention to the “imaginary archaeology” by which art “illuminated” objects in their original context and in the new context of “another space and time,” a formulation highly suggestive of Foucault’s later concept of heterotopia. For Jouffroy, the “archaeology of the present, alas, makes of every object its own cemetery.” At stake here were two contending views of the non-traditional art object. For Ortiz, destruction released the spirits of colonialism and capitalism from man-made objects; while for Jouffroy, the resulting art object became the cemetery of, rather than occasion for “active thinking”. If Jouffroy rightly pointed to the limits of archaeology, tout court, Ortiz saw how archaeology could become a deconstructive activity rather than one premised on a metaphorical reconstitution of a missing whole.

Raphael Montañez Ortiz: Resonances from the Concrète, by Jesse Lerner

An Interview with Raphael Montañez Ortiz, by César Ustarroz

Essays

- Recent Archival Engagements with the War to End All Wars, by Scott MacDonald

For some film artists committed to working with archival materials, the hundredth anniversary of World War I was an irresistible opportunity to retrieve something of the historical and cine-historical past and to conjecture how that past has continued to inform the present. Certainly, for artists and writers of all kinds, the war represented a major turning point. Its immense human and economic costs (close to twenty million people died as a direct result of the war) and the sense, in the wake of the signing of the armistice in November of 1918, that nothing of substance had been accomplished by this disaster—indeed, that a second world war might be a distinct possibility—invigorated artistic and literary rebellions against the ways in which the arts had functioned in culture during earlier centuries and was crucial in instigating what we think of as modern art.

Given that the international catastrophe of the war to end all wars occurred just as cinema was evolving into the western world’s major source of entertainment, as well as a source of information, it was virtually inevitable that filmmakers would take their cameras into the field to document what was occurring during the build-up to the war and during the war itself. And, a century later, the lure of the archives where much of this documentation ultimately found a home has made possible a set of remarkable cine-explorations of the war and cinematic representations of it.

Filmmakers covered in this essay include Bill Morrison, Angela Ricci Lucchi & Yervant Gianikian, Peter Jackson, and Sam Mendes.

- Memo from the Future: The trans-temporal work of Kirk Tougas, by Donald Brackett

When is appropriation appropriate? Kirk Tougas

Every film is a tattoo etched on the surface of time, some more so than others. Certain filmmakers, however, eschew entirely the tradition of distracting the audience from awareness of the fact that they are watching and are customarily invited to submit to a willful disappearance into a real or life-like story. These consummate others instead tend to invite the audience to relish and savor the viewing experience as a sequence of electric paintings, one which may or may not contain a program beyond the temporary tattoo incised onto the dream space they occupy while in a theatre. Some of them, such as Kirk Tougas, go even further: they implore the viewer to actively engage in watching their own watching.

- Found Objects, Generative Footage, and Machinima: Peggy Ahwesh’s She Puppet, by Michael Betancourt

The basis of machinima, as in filmmaker Peggy Ahwesh’s video She Puppet (2001), has a specific contingency about its origins: did Ahwesh herself play the video game Tomb Raider to gather the footage she used? This question gets to the historical definition of machinima’s development out of recordings made using the demo mode for games such as Doom or Quake in the mid-1990s; the transformation of video games through reprogramming and captured gameplay constantly returns as a refrain in their critical appraisals. There is no clear and definitive answer to this question from within the video; the answer is unimportant to her use of this footage. Although what Ahwesh finds for She Puppet is a direct product of past production (the game)—thus resembling found material—at the same time, the shots in She Puppet are entirely new, original, and unique to her video.

By handling the imagery created in Tomb Raider as cinematic material, rather than gameplay, her video has a different focus than those approaches based on game art. However, this interactive environment of the game poses an immediate problem for the familiar conceptions of the readymade material of the archive used in avant-garde practice simply because there is no footage being found.

- The Rejection of Camera Shooting and Its Implications for Found Footage Filmmaking in the Work of Jay Rosenblatt, by Marta Rychter

Found footage filmmaking can be described as the act of finding new meanings in pre-existing images, critically re-working, re-using, examining the original context of the found footage and composing a new film out of it. The first question that occurs to me is: Why would a filmmaker prefer reusing pre-existing, found images to shooting his/her own? It is the particular collection of found footage films made by Jay Rosenblatt that triggered my interest in this non-camera aspect of the field in the first place.

Jay Rosenblatt directly draws to my own concerns by saying: “It is a very different process to work with images that already exist than with something you shoot”. Discussing found footage filmmaking in the context of rejecting the camera offers new insights into this practice.

- Finding One’s Feet: A pair of Ernie Gehr’s found footage videos, by Ken Eisenstein

Ernie Gehr’s 16mm filmmaking activities lasted for more than a quarter of a century (1967-2004). During all that time, he only made a single found footage film in that medium: Eureka (1974). However, since the beginning of the 21st century, and Gehr’s turn to the use of video, there has been an exponential increase in his attention to this practice. As a way to begin exploring the still too unseen late work of a pivotal figure of the American avant-garde, this essay takes up an in-depth study and close reading of two of Gehr’s found footage videos: The Astronomer’s Dream (2004) and Good Grief ! (2015).

ARTICLES & INTERVIEWS

- Remembrance of Films Past: Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart (A Work of Found Scholarship), by Justin Remes

- An Interview with Guli Silberstein, by José Sarmiento-Hinojosa

- The Uncanny Collages of Stacey Steers, by Marie-Pierre Burquier

- An interview with Hugues Sanchez, by Francesca Veneziano

- Cleanse, Tone, Moisturise (Conceal): As the Image is Concealed, its Intentions are Revealed, by Joanna Byrne

- Sokurov: Whispers from the Archive, by César Ustarroz

Book Reviews

· Ism, Ism, Ism: Experimental Cinema in Latin America, by César Ustarroz

· Toward Fewer Images: The Work of Alexander Kluge, Matthew Cole Levine, by Matthew Cole Levine

DÉMONTAGE. Films to Break Projectors, by Tim Grabham aka Iloobia

Artworks

by Keitaro Oshima, Anne-Marie Bouchard, Leandro Listorti, Giuseppe Spina, Lee Hangjun, Alex Faoro, Francisca Duran.