Interrupting the Amnesic Race Towards the Future: A Conversation with Rick Prelinger

Rick Prelinger is perhaps best known as the founder of the Prelinger Archives, originally a collection of ephemeral films or useful cinema, currently focused on home movies and outtakes of a diverse nature. Acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002, the Prelinger Archives has been a crucial resource for filmmakers and scholars for decades. However, its availability has never been limited to specialists. It holds footage that can be found nowhere else, granting as much importance to access as to preservation, being a toolkit for revisiting documents of the past that might otherwise have fallen by the wayside. The archive is truly one of a kind, and so is Rick Prelinger. He is so much more than a custodian of moving images and sounds: he is also a filmmaker, writer, educator, curator, open-access advocate, and above all a keen observer of the present. Where most see only outdated imagery of everyday banalities and images of a bygone era, Prelinger is aware of how revealing these old images truly are. In his own films, history, place, and their complex relationship take center stage. From his first work, Panorama Ephemera (2004), to his Lost Landscapes events (2006-present)—participatory screenings of his feature-length historical compilations of urban landscapes—he steers clear of nostalgic reverie, choosing instead to counter stereotypes and defamiliarize the past with its own photomechanical remains. As a writer and speaker, he has explored some of the most pressing issues surrounding media transformation, the material realities that archives face, and the need for archives as sites of contestation. For Rick Prelinger, to preserve is to interrupt the race towards amnesia.

Sibley Labandeira: Rick, you are an archivist, a filmmaker, a writer, and an educator. I imagine that all these roles are interconnected, but is there a primary one? Is there one activity that has been the motor for all the rest?

Rick Prelinger: Interesting question. I became an educator late in life because I had the opportunity to apply for a job at the University of California, Santa Cruz, which was a dream job. I’ve been a writer for about thirty years, but very sporadically: it’s only in recent years that I’ve been writing a lot more. And then I became a filmmaker about twenty years after I became an archivist. My first film was Panorama Ephemera. People ask how long it took, and I say “twenty years and nine months” because it was everything that had been on my mind for so many years. But I think the relevant thing is that I started collecting film in 1982-83, and that’s really been the gateway to almost everything else I’ve done in my life. Before that I was a college dropout, and I was a typesetter working in the printing industry, now an extinct job.

S.L.: How did collecting start for you? I mean, almost any person can accumulate a few things that are similar in nature or that are connected for that person, but there’s a moment when that gathering of objects becomes a collection.

R.P.: Yes!

S.L.: So, when would that be for you? Is there a specific moment?

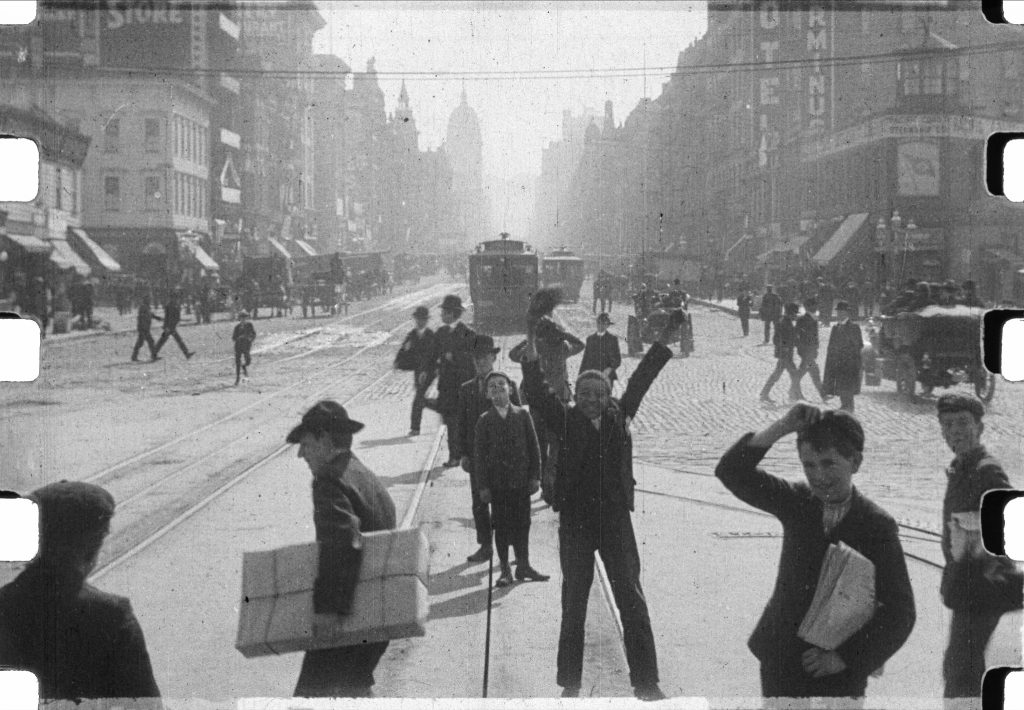

R.P.: I have often told the story that I was working on a documentary film (Heavy Petting, Obie Benz and Joshua Waletzky, 1989) and part of my work on that film was trying to understand gender roles and sexuality in the post-World War II era, and I turned to educational and sponsored films to understand that. But there was this moment of media transition that was happening, and media transition can be difficult, but it can also be incredibly formative. Because when film was seemingly replaced by videotape I realized, as I was looking for non-traditional film sources, that most of these sources were redundant and people didn’t want them. So, there was this opportunity, and I was so interested in this parallel world of useful cinema in the past. I was so interested in the glimpses of urban landscapes, labor, and the city as it had appeared in these films. It was irresistible to begin collecting and, when I had a hundred or a few hundred films, I began to realize that this was a resource, more than just a crazy thing.

S.L.: Are you still gathering new material? I ask because of the acquisition of the Prelinger Archives by the Library of Congress.

R.P.: When the collection was acquired by the Library of Congress, I felt a great sigh of relief. I didn’t have to be custodian of 200,000 cans any longer. But a few years later I just began again… I had collected home movies earlier, but not extensively, and I was so fascinated with them that I began to collect, maybe irresponsibly. That collection continues to grow because people give us so much material. We are swollen with film! We think we have about 40,000 home movies. In addition, there’s material that comes in that nobody wants, industrial material, filmmakers’ material, and then also the Library of Congress offered us back material that wasn’t in their scope, like outtakes, and it turns out that outtakes from industrial films from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s are astonishing! They’re images, evidence, and truth that’s not in completed films, and they’re useful for so many things. So, we’ve had a great deal of fun scanning them.

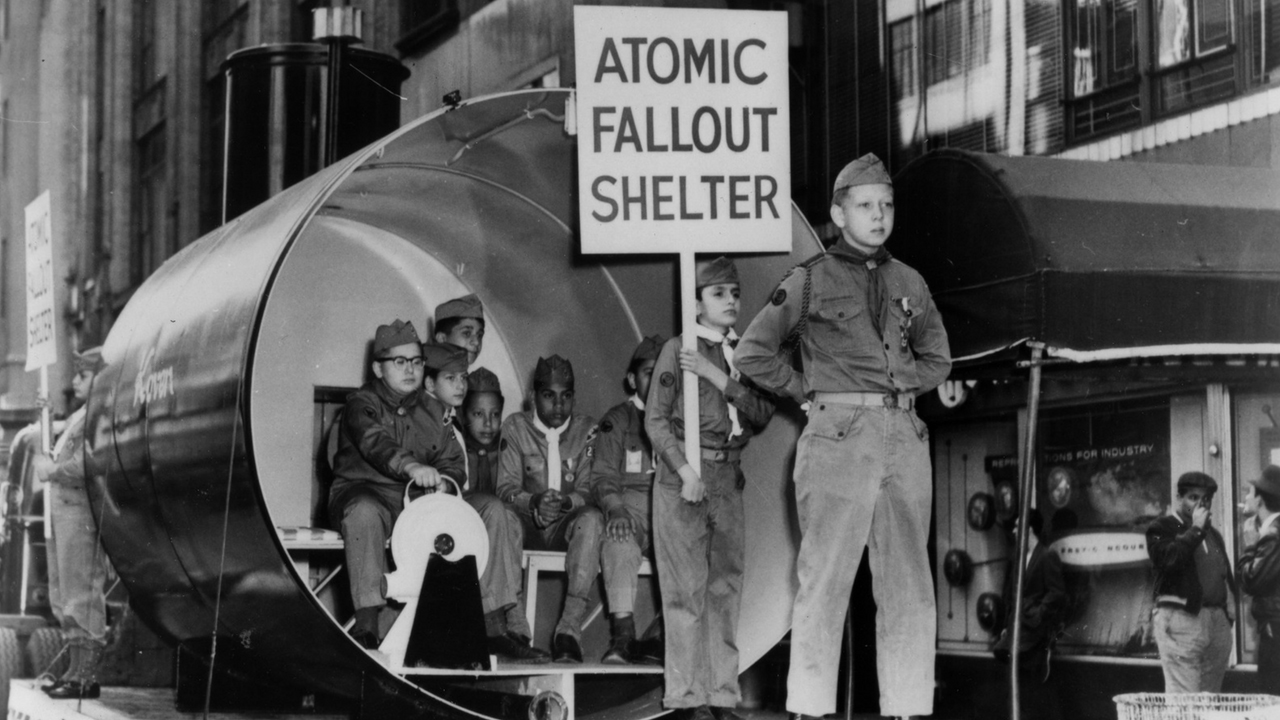

S.L.: I love outtakes! In fact, I was going to ask you further along—just out of personal curiosity—about The Atomic Cafe (Kevin Rafferty, Pierce Rafferty, and Jayne Loader, 1982), but it seems pertinent now, since some of my favorite moments in that film are precisely the outtakes with the clappers and that sort of thing.

R.P.: Yes!

S.L.: They point to the fact that all these images are constructed and how, beyond the final film, there are always things that have been left by the wayside, and they’re so interesting!

R.P.: Exactly! I’m going to digress and tell you a very brief story about that clapper in The Atomic Cafe. They used a film made by the Navy where they speak to the Indigenous inhabitants of Bikini Island who give consent for themselves to be displaced, and they say they’re going to leave. That clip was furnished by the National Archives to the filmmakers and afterwards, at some point, I am told it was thrown away. The rationale was that “Oh, it’s just another outtake. It’s just an additional copy. It’s not historically relevant.” But the thing is, what makes it historically relevant is the clapper board, the fact that it was rehearsed. And that’s the story that it tells. But that clip on its own doesn’t exist anymore.

S.L.: Wow! Scenes like those are one of my favorite things, they kind of give me a jolt when I see them somewhere. I’m so glad that you’re gathering outtakes. I think it’s essential.

R.P.: Actually, Pierce Rafferty and Jayne Loader gave us the outtakes to The Atomic Cafe, so we have been scanning as many as we can here.

S.L.: What an incredible resource! It kind of ties in with something I wanted to ask you. I’ve read that first—and you’ve kind of said it already—you were very interested in different kinds of ephemeral movies, like industrial movies or educational movies, and then your interest shifted to home movies and amateur filmmaking. Would outtakes now be a new focus or are you focusing on something else?

R.P.: My partner Megan Shaw Prelinger and I co-lead a group of eight people who are working on film preparation, scanning, and metadata—all in the cause of making many thousands of new films available online for research, viewing and reuse. So, everybody’s involved, but there’s a special interest in material that we can make available online, because we only collect something if we can make it available. We are finding in the process that there are some materials that are too sensitive to put online. An example would be Indigenous or Native traditional knowledge that is not meant to be shared, or images of animal abuse. We would be very reluctant to be a vector for badness. But we really want to build a comprehensive encyclopedia of the world in the 20th century with as much imagery as possible for research, for filmmaking, for people that just like to look at that stuff. And so home movies are the primary concentration. Second would probably be what we used to call ephemeral films, what I now call “useful cinema,” taking my lead from the Canadian scholars Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson. And then outtakes, just because we have a lot of outtakes. What we don’t do are entertainment materials, we don’t do features. Here and there we do favors for filmmakers or institutions and scan materials we can’t offer online. This kind of film has the potential to get people away from stereotypes, and to allow people to view and to understand histories that are still not well documented. So, in home movies we’re focusing on families of color, rural people, movies made by children, movies made in schools, movies made in the workplace… These are all really, really interesting. There are many more than one would think, so we’re trying to build a public repository of much of this material.

S.L.: That’s fantastic! Both that you’re covering all these areas, and that accessibility is one of the priorities. It reminds me of something you said in an interview for Synoptique journal, where you mention that you think of films “as spines on which images and sounds hang waiting for reuse.”1 I thought that was a wonderful metaphor. Do you still think of films like that?

R.P.: Yes, I wrote something about the process of putting on a Lost Landscapes event, published a short while ago, where I said that one of my objectives is to encourage people to look at images rather than films2. The construction of what we think of as a film is so strange to me. It’s as if cinema in 1915 was on a railroad track and somehow switched sharply over into narrative fiction, with some allowance for documentaries. But even documentaries these days are mostly narrative fictions of their own kind. And one of my longtime objectives is to get people to think about images and sounds in themselves, and to think about films as assemblies. When I studied semiotics, when it was just coming to the United States, and film theory in the 1970s, I had a mentor named Bertrand Augst—who was the spirit who encouraged the foundation of the journals Camera Obscura and Discourse—and he always taught us to think about films as assemblies of semi-autonomous segments. I’m not a big theoretician, but it perfectly prefigures what I do now: take these things apart, think about them, and what can we do with the pieces.

we really want to build a comprehensive encyclopedia of the world in the 20th century with as much imagery as possible for research, for filmmaking, for people that just like to look at that stuff

S.L.: It makes me think of one of the things that surprises me about my students. When I use film as an umbrella term, they ask me things like, “But is a documentary a film? Is a short film really a film?” and I say, “Of course they are! Why are you only allowing a very narrow margin of phenomena to be called film?” Maybe a good way to go about it is to focus, like you do, on images and sound.

R.P.: I think it’s reassuring that there be an umbrella term. But when you think about home movies, they are definitely not cinema. To call home movies a portion of cinema is completely reductive. Home movies are life.

S.L.: Thomas Elsaesser, writing about the work of Harun Farocki and his use of industrial films, proposed thinking of films not so much as texts but as events, in the sense that they have their own temporal and spatial coherence, but they are a process in the sense that they are multi-layered and they involve planning, but also accident and coincidence.

R.P.: It’s funny because I’m glad that people are now doing textual analysis of these films that were kind of always taken for granted. Bill Nichols says somewhere that industrial and educational films are simpler and less worthy of analysis than documentaries. I think they are texts, but I like the idea of events. I also think of instruments. I used to think of useful cinema as something that documented efforts to convince and efforts to persuade. But, really, it’s not that they’re documentation, they are the instruments themselves. And I kind of didn’t get that for some years. But the text thing, I’m not an art historian, I’m not conversant there, but at breakfast yesterday I was reading in the New York Review of Books an article about the art historian Svetlana Alpers, who is credited with kind of trying to push back on the idea of textualizing visual arts and thinking rather about enunciations, which are kind of like events. I think about performance, I think about visuality, and we should be thinking about films that way. If you think about the kinds of films that I’ve collected over the years, the first stage of scholarship is inventory, and people writing a lot of articles about who made this—what are the films made for Fiat, for instance, what are the films made by this production company or by this woman who’s been rediscovered. And then the second stage is sociohistorical, sociocultural. And then we never get to the stage of thinking of these films with a lot of autonomy, thinking about their aesthetics, thinking about them as art, and maybe that’s where we should be right now.

S.L.: I think we should always try to come in through different angles, because they are really complex objects, these images.

R.P.: But there are too many films for people to grant complexity to all of them. So, it’s a tough one. I hope that one day these films move from the periphery to the center.

S.L.: I’d like to ask you about your films, which of course use many different sources and combine them in very interesting ways. How would you classify your films? I ask because there are several terms for when people reuse footage: there is found footage, compilation, archival film, archiveology… Is there a term that you feel more at home with for your own film production?

R.P.: I haven’t really found a descriptive term that I really like. I don’t like the term found footage very much. And, in some ways, it’s appropriate that it’s kind of been taken away and it’s used for The Blair Witch Project (Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, 1999) and the horror film thing. I heard of found footage in the 1970s, talking to friends of mine who were film students who taught classes. The idea was literally that there was a lot of film lying around, like scrap paper, and that people would pick it up and do something with it. It was very specific. It was about actually finding something, you didn’t go do research, you didn’t go to archives. There was a box on the street, like Ernie Gehr finding his perfect film, Eureka (1974). There was often footage hanging around in the equipment laboratory of a film school, you know? Then found footage became an umbrella term. Maybe because it has two Fs, the alliteration, it sounds good. But it used to describe a very specific means of access. And now, archival film? What is an archive? Of course, that’s a whole big issue. We’re kind of an archive, but that’s a contested term. And now, when artists go pick up scrap iron on the street, that’s an archive, so I don’t know. A compilation? That’s so old-fashioned. I don’t really know.

S.L.: I ask because I’m interested in the reuse of footage and what happens to old images in new contexts, and I always feel that language falls short. It’s hard because, for me, the foundness of these films is perhaps the least interesting aspect.

R.P.: Right! And this is what Jaimie Baron gets at, that we don’t care about provenance anymore. That archival is an effect rather than a cause. I think it is a really smart insight of hers. But also, the idea of reuse, as I’m speaking to you now, for the first time, I’m realizing that a lot of what I use isn’t reused because it’s never been used. A lot of these outtakes were rejected at the beginning, they had no use. Home movies were meant to be seen by a family, but maybe they weren’t. Some of these films have never been opened up, they just came back from the lab, some of them were never even developed. I mean, who cares if we’re that precise? But you are putting me in an interesting thinking place here, because there’s a way in which, to talk about sorting out genres, or modes of practice, then film feels kind of reductive. Bertolt Brecht says somewhere that the contemporary theater takes all these different elements and it theaters them all down. In other words, it’s a reductive process. And I love the idea instead of film sort of reaching out little tentacles into the world and engaging the world.

S.L.: I want to go back to your films. Another interesting aspect is that many of them are what we could call place-based. Why that focus on specific places?

R.P.: So much of my fascination with images goes back to when I was young. I grew up in New Haven, Connecticut, and New Haven was privileged in that it got the largest share of federal money to redevelop its downtown area. So, they tore the heart out of the city. The city that I grew up in as a child was filled with construction, old buildings that were being torn down, new highways, some really exciting buildings downtown, parking garages, Brutalist architecture, famous buildings that you could ride around in the elevators and look down at the street. And I became very interested in what the city used to look like, because I’d seen a little bit of it as a very young child, and so these were images in my head. I would go to the public library where they had a photograph collection made by the redevelopment authority, and I would look at these pictures with a magnifying glass to see the details of what cities looked like, what did the license plates look like, what were the headlines on the newspaper. All of this fascinated me and, as I’ve said before, the first film that I collected was a pedestrian safety film made in Oakland where in the center of the image were simulated accidents, but on the periphery of the image were all these wonderful scenes of a city with which I was very familiar. I was very interested in landscapes, urban landscapes, landscapes that were lived in by people. I was interested in places like Detroit, where almost every street has a history of conflict, it’s a very conflicted space. So, I think I began collecting film to collect and recreate landscapes of the past. The first film I made, Panorama Ephemera, was about history and place. It was this sort of parable of the history of the United States, North America as told through these 64 sequences, and many of them foregrounded place. And then No More Road Trips? (2013), nine years later, was totally about place. I wanted to find the most evocative images of what you could see along an east-to-west trajectory. And now I do these Lost Landscapes, and that’s like the fly trap. I started doing them in 2006, when some friends who ran a local history project said, “Could you show some historical clips of San Francisco?” I did, and a lot of people came. It became locally very popular. I just did the nineteenth version of San Francisco on Monday and Tuesday, and the twentieth will premiere in December. I’m working on a more rigidly structured film that will paradoxically give the clips more freedom to play.

S.L.: I saw a video of one of the screenings of the Lost Landscapes in San Francisco, and what was really striking to me was the audience participation.

R.P.: It was crazy! The audience has changed a little bit, these are people that we did not know as well, and they were wild! The room was rocking! It was almost unsettling. And I think that people come to this—I mean, they come for the subject matter—but I think people also come because they know that they can transgress, because it’s a space that’s open to talking in the dark.

S.L.: Speaking about transgressing, I have also read that you attempt to interrupt or problematize myth. Could you speak a little bit about this idea of interrupting myths?

R.P.: Yeah, I love interrupting myths. I love when I find footage or films that counter stereotypes. So, footage of a Black man in the 1930s owning an airplane, footage of Black people and white people eating lunch together when they’re working in Baltimore in the 1950s. In a film I showed earlier this week, there’s a gag reel that was made by a local TV station from 1965 or 1966, and they used the song “Downtown” by Petula Clark, which is supposed to celebrate downtown, but they show footage of how disorderly and decayed San Francisco’s downtown is, they depict sex shows and strip clubs… Right now, there’s a whole doom loop narrative in San Francisco, a story that San Francisco is a horrible place and it’s all messed up, and to show that people were thinking the same way in 1965 helps us maybe feel a little better about where we are right now. So, yeah, constantly. In the film No More Road Trips? I wanted to help people think about different kinds of travel, that there’s pleasure travel, but there’s also migration, that people have to migrate, that people have always migrated, and that Native people have had their lands taken away and they have been forced to move. There are many forms of road trips, and as climate and energy become more complex, we may not be able to do that anymore, which is why the film has a question mark in the title. And also, to show cities as they really were rather than as we imagine them. When you engage in nostalgic discourse, which isn’t a horrible crime, usually you’re showing people images that reinforce preexisting ideas, received ideas, but it’s much more interesting to show people films about the past that make them think a little differently about the past.

S.L.: I think that’s exactly why some so-called found footage films are so important and so interesting, because they counter this nostalgia. It’s a way of seeing the past through the material left behind.

R.P.: I also think that when you show material of the past in very high quality that’s richly detailed, when we do these 5K scans and we really try hard to make material look good, that also challenges the idea that the past lives in some zone that’s characterized by image deterioration and traumatic effects that have been visited upon the film, all the injuries that the film has received. I love it when it’s possible to show something from the 1930s, 1940s, or 1950s that looks as if it were shot yesterday. I think it creates a defamiliarizing effect, and I’m very much into defamiliarization. It’s probably one of my guiding principles.

S.L.: It makes sense because, to begin with, using older footage is already taking it out of a context so radically that there’s already a process of detachment, at least.

R.P.: Yeah. I mean, I did a screening this summer in a park—I’d never really done a big outdoor screening before—and we learned there were over 2,000 people there, for part of a series where people go to see movies in the park. I don’t think they knew what they were coming for. The rest of the films in the series were very intense Hollywood productions, with deep sound design and the kind of production that just takes you by the head and shakes you, right? And then they saw my quiet, strange film that encouraged audience participation. I think people really didn’t know what they were seeing, but I felt like their expectations grew as they were there, and it made me so excited.

S.L.: Also, it’s not only film that does this or images that you can do this with; an archive, in a sense, is already a kind of an apparatus that works with defamiliarization, as do institutions like museums or botanical gardens. They are collections that take things from different sources and put them in a new discourse, which in a sense is artificial, but it’s a discourse that we’re very used to. Something is already defamiliarized once it’s in an archive.

R.P.: It’s true, but I wish that process worked a little bit better, because from most archives very little film comes out. Because it’s just so difficult, and it’s even harder in Europe! Our copyright laws [in the US] are much more permissive. You have so much more to deal with in the EU, and it’s very unfortunate. When I worked in San Sebastian (at the Elías Querejeta Zine Escola) in January 2024, the students and community members made a film about the region, and to work with they only had a selection of films that had been cleared by the archives for use. They weren’t allowed to roam freely because of copyright and other issues, and so, in a lot of ways, what you’re saying is absolutely true, but it’s a little more conceptual because you can so rarely see the entire canvas that an archive contains. And we should be able to do that. We ourselves have had the great privilege of pulling something off the shelf and looking at it and transferring it to video, or now to digital, and making it available, if it was free to do so. And most archives don’t have that freedom. So, in a sense, archives haven’t been realized. We don’t really know what archives could be because of this enclosure.

S.L.: I want to ask you about something you wrote: “Whether or not we consciously acknowledge it, archives make historical interventions. We intervene in the present by foregrounding the past and infusing contemporary culture with the historical record. We cannot deny a process that exists whether or not we embrace it.”3 I really liked that passage, and I’d like to know, how do you work from within the archive with this in mind? Archives intervene, there’s no other way around it.

R.P.: Well, I would have to qualify that and say that it’s not an abstract thing, because archives intervene only if people can touch their contents. And when I say touch, I mean not just look at, not just listen to, but actually touch. If you have a painting or a sculpture that’s on the other side of a fence, you can look through the holes in the fence, but you can’t touch the sculpture. And with film, you have to be able to touch it, which means edit, make something out of it. If you touch a film, you touch the edit list, you touch the continuity. Again, it’s this fact of defamiliarization: when you take a piece of the past and you put it into the present, it’s an intruder. It may be a benevolent intruder, but it is an intruder, it’s an interruption of this amnesic race towards the future that we’re involved in. Or it’s an interruption in the process of decoration, where images and motifs from the past are used simply to make this world look prettier or more varied or more eye-catching. But to interrupt the passage of time towards the future with a historical image that defamiliarizes the present, that’s a really, really important process and I want to encourage it. History should be infrastructure. History should be like air or water. It’s just there. You should be able to walk by a building and know everything that happened in that building. It would not be good for the real estate value of many buildings, but history is so emancipatory. To know that something was fought over, to know that at this point in time this land was expropriated from Indigenous people… Around the corner from where I live, in a very ordinary middle-class neighborhood, there was an anarchist bombing in the 1920s. Irish anarchists blew up a building by mistake, and you wouldn’t imagine it! I think that kind of thing is fascinating. And, by the way, everybody’s interested in that sort of thing.

S.L.: You were just at the Association of Moving Image Archivists’ annual conference. I’m curious, what were the topics or concerns that you would highlight?

R.P.: There were a number of conversations that seemed to predominate, two in particular. One of them was that there was a lot of visibility of archivists from emerging communities, because of the community archives movement. So, there were a lot of younger archivists, especially archivists of color. There was one group called Entre, which is on the US/Mexican border, in the Rio Grande Valley in South Texas, and that’s a community archive that assembled a program of very short home video sequences, shot by people, mostly Mexicanos who lived in the Rio Grande Valley, and they had been chosen by the families themselves as an ofrenda, an offering for people no longer with us on Earth. It was very, very moving because these home videos were not disassociated from the people who made them, who had selected material that was emotionally and spiritually significant, and it was so strong! There was the community archives group which is a very exciting development; we hope that they can survive because a lot of them have no money. The other big topic was AI. You know, there’s been this statement in the United States from the Archival Producers Alliance about best practices involving the use of generative AI and documentary film. They had a whole panel, and at the last minute, the keynote speaker, a European who was on the panel, couldn’t get on his plane, so they asked me the night before to join them and talk about the ethics of AI. I’ve thought about this quite a lot; we’re in San Francisco, of course, where automatic cars without drivers are moving around all the time. So, we think about AI a lot, and I spoke, I had a few idiosyncratic things to say about that.

S.L.: Would you share some?

R.P.: I said that while we should be very concerned about deep fakes and about people kind of rolling their own history instead of using existing history, the ethics of AI were not the biggest ethical problem facing archives. The biggest ethical problem right now is how to preserve the institutions that preserve culture. Because archives are extremely vulnerable right now, whether it’s the archivists who were laid off at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in LA—big issue, they got rid of a lot of archivists and librarians—or the archives and libraries that have been destroyed in Gaza, or you name it. Very vulnerable. And in the United States, metadata itself is under attack; there are forbidden words and concepts that can’t be expressed in federally-funded projects. Many historical images are being deprived of online presence. If we work in archives and we think that the world supports us, we should think again. I said some other things; I said, “Look, if archives are very concerned about being replaced by fakes, by general AI, then why the hell do archives make it so hard to access their material? Why do they charge so much?” Because when they charge so much and they demand all these papers and clearances, they’re driving producers into the arms of generative AI. Of course, nobody had an answer for that. We give away our footage, we’re very privileged because we’ve been rewarded for giving away our footage, and we’ve made some sacrifices. A lot of other people have made millions of dollars reselling the material that we give away for free, but it’s still the right thing. So, we had some interesting conversations.

S.L.: I think this idea of the fragility of archives is paramount. It seems like support for archives, and cultural institutions in general, is getting harder and harder to secure, which is paradoxical in the sense that we are creating more material than ever.

R.P.: It would have been a little different if archivists, instead of professionalizing, had worked harder to try to distribute the responsibility for collecting and preserving to the population at large—if it was clear that we all had a role in preserving the history that was around us, and that maybe there were institutions that could help us but not simply take it over. Right now, many members of the public are under the illusion that somebody’s doing everything, taking care of this. And they actually get mad when they hear, “I can’t get my favorite movie anymore because Netflix has taken it out.” So, we really need to think. Just like addressing climate change now, we can’t fix it by recycling, or by taking fewer airplane flights. It’s bigger than that. But when it comes time to deal with the consequences and remediate. It’s going to be up to all of us. And it is up to all of us to save culture. And we need to think about a new matrix, and honestly, I think archives are key; archivists can make a very good argument that we are repositories for historical facts. But I think a lot of people just don’t care, and it seems, when people think about how much culture and how much media is being produced, I think it induces a certain kind of defeatism, because it’s not possible to save it all. And if we admit that it’s not possible to save it all, that also is liberating, because when there’s a gap in the archives, when something is missing, loss itself is formative. Loss gives rise to new efforts, new kinds of histories, new kinds of rescues. I’m resigned to not being able to save everything. I don’t think we could anyway.

S.L.: No, that’s another myth, that everything is savable, and in fact, even when we save a large quantity of objects, interpretation is still so important. It is not just about what you have, because images don’t live in isolation; they are products of context, of tensions, of power relations, of so many things.

R.P.: And there’s personal spatial disempowerment, which I think gives rise to a sense of collective spatial disempowerment. If you’re a young person you don’t usually have a big house; if you’re in Europe you probably still live at home for many years because of precarity. And I think that produces a profound sense of heritage disempowerment. Where are you going to put it all?

Loss gives rise to new efforts, new kinds of histories, new kinds of rescues

S.L.: If you don’t mind, I’d like to go back to The Atomic Cafe, because as I said before, it’s a film that fascinates me. I read recently that at the time of the film’s production, you were housemates with people working on it, and I thought that was an interesting crossing of paths. Taking into account that the film was released in 1982, which is when you founded the Prelinger Archives, it made me wonder if there was a community for that shared interest in old ephemeral footage and this kind of thinking, or was it sheer coincidence?

R.P.: So, I went to high school with Pierce Rafferty. Pierce and his brother Kevin made The Atomic Cafe originally with Stewart Crone, another classmate of mine, who came out to work with them. Stewart left the project and Jayne Loader came on. When we were in high school, Pierce and I had a friend in common named Danny Cahn, who’s no longer living. Danny Cahn’s father was a communist who produced pictorial histories of labor, and he made very heavy use of public domain materials in the US National Archives. Danny told us about this, and we all became fascinated with the idea that there was this huge repository of public domain materials. And it was precisely the work of this man, Danny Cahn, that inspired Pierce Rafferty to go to Washington with his brother and with Stewart, and look for public domain material relating to propaganda. Initially, The Atomic Cafe was about propaganda, and then it became focused more specifically on atomic propaganda and persuasion. And it was a huge success; that was the time when there were many demonstrations about nuclear disarmament, big marches in New York. The Atomic Cafe was shown on Capitol Hill in Washington to US congresspeople, it was shown in a hundred cities in Japan, I believe. It was a well-timed release and Norman Lear, the TV producer, who at that point owned a movie studio, came to the Raffertys and said, “make me an Atomic Cafe about sex and romance” (which would eventually become Heavy Petting), and that’s when I was hired as research director. I was housemates with Pierce Rafferty and his then-partner, Margaret Crimmins, who was the sound editor. So, although I did not work on The Atomic Cafe, I was very, very close to it and went to many of the screenings, and it was a very chaotic process. In New York everybody was a little crazy.

S.L.: Thank you for sharing that with me. Can I ask if you have any films in development now or plans for a movie in the future?

R.P.: I’ve always wanted to do a film that uses archival material to reconstruct a hundred classic rhetorical figures. I don’t think I’m up to doing it, but it would be so great to try to find that. I mean, it’s been done with hip-hop, of course. I suppose it’s one of many films that I’d love to make. But, right now, our grant to scan films lasts another seven months after the beginning of the year, and then we hope to be renewed and get some additional funding. I’m co-managing eight people and it’s a lot of work. But we’re building this incredible body of material to work with, so far 9,000 films. Will anybody ever touch it? That’s the other question. We often think too many people make work with footage, but in fact, not nearly enough people do.

Endnotes

- 1. Cook, Sophie, Bartolomé Herrera, Beatriz and Robbins, Papagena (2015). ‘Interview with Rick Prelinger,’ Synoptique, Vol. 4, N0. 1, pp. 165-191, cit. p. 167. Link (accessed February 8, 2025)

- 2. Prelinger, Rick (2024). ‘History is Made at Night,’ The Back Room, October 12, 2024. Link (accessed February 8, 2025)

- 3. Prelinger, Rick (2009). ‘Points of Origin: Discovering Ourselves through Access,’ The Moving Images Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 164-175, cit. p. 165.