Lost in Time: The fate of footage in the digital age

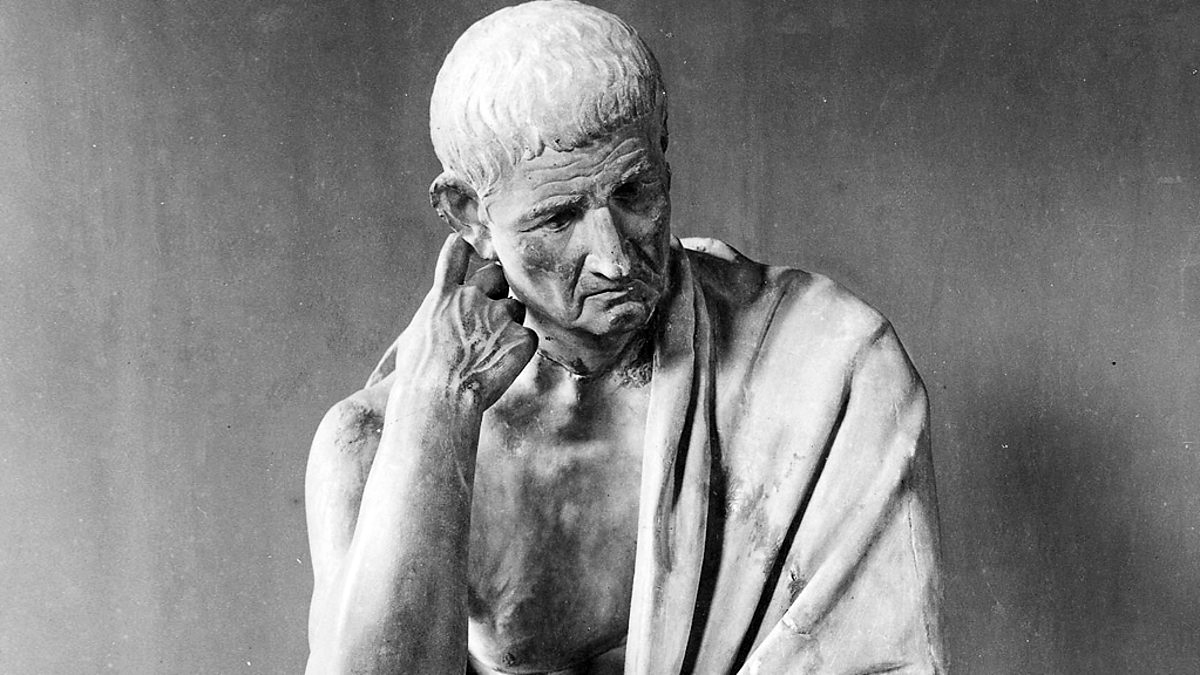

The camera introduces us to unconscious optics, just as psychoanalysis does to unconscious impulses.

—W. Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’.

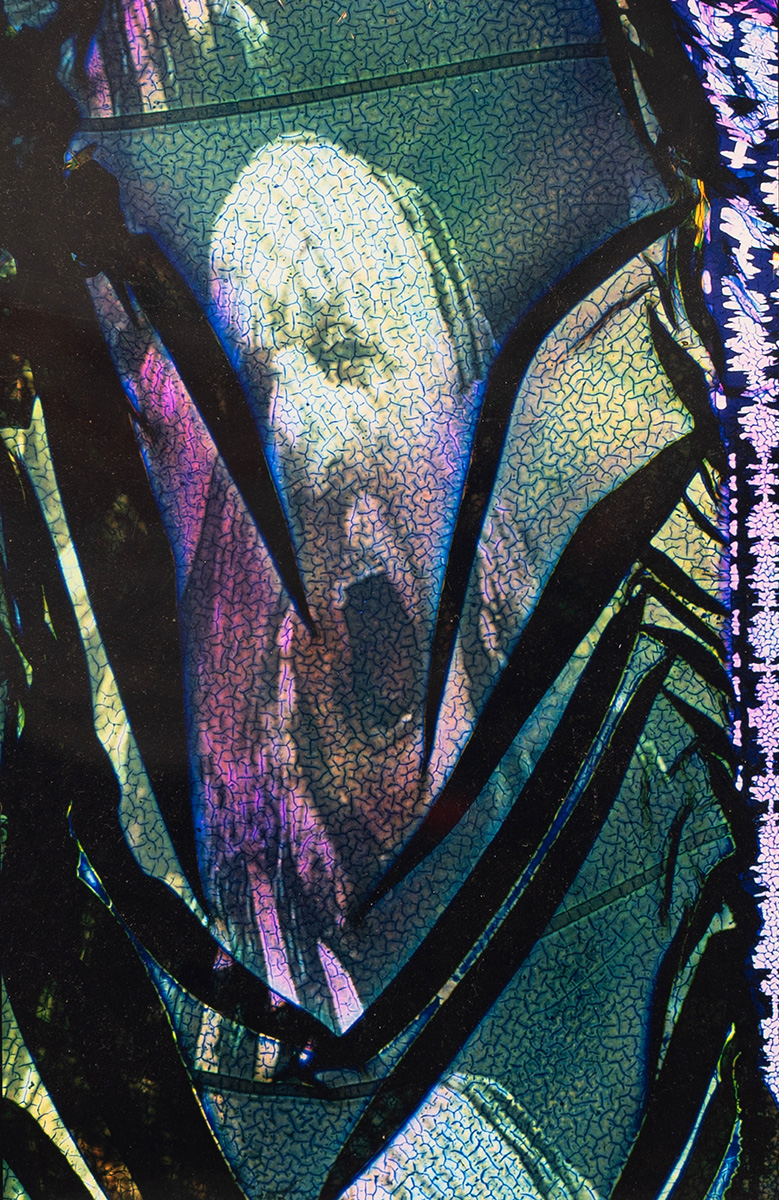

In his Artifact (Circa 2006), a video work made in 2018 which posits the dilemma of embodied meaning in the midst of enforced technological obsolescence, filmmaker and Pacific Cinémathèque founder Kirk Tougas provides something of a Cassandra-like harbinger of the shape of things to come, while stressing that it’s largely up to us how much we submit to the allure of a high-tech embrace. In that work, he draws our attention to the future of memory and the archaeology of identity, and offers us a cautionary view of ourselves that makes us tourist-like aliens on our own planet. How will those future tourists perceive the archaeo-psychic aspect of who we were and what we did? Tougas takes a pragmatic but also profound approach to answering such probing questions:

Consider a world where all our human communications are represented solely by numbers, a digital world. Imagine a future archaeologist finding a DV cassette from hundreds of years in the past, with real found footage, full length and uncut. Imagine trying to decode this ancient digital object, codecs unknown, obsolete, hardware long lost. How to crack the code. A.I algorithms can scan raw data, consult image-banks, repair bit-rot, reconstruct the artifact. Is the result authentic, or fiction? The dawn of self-by-numbers: what human fragments of fugitive narratives remain? (Tougas, 2006)

Virtually all of the experimental filmmakers I spoke to in researching this essay share a similar perspective on their ever-evolving medium. For one thing, none of them like being called experimental filmmakers, preferring instead to be considered visual artists who do various things with film. The second overlap was their perceived need to enlarge our understanding, not just of what constitutes found footage and what we do with it, but also our appreciation for what constitutes footage per se. Whether pigment or pixel, everything hinges on the artistic choices we make, and on the aesthetic fact that we control them rather than the other way around.

Since our contemporary cultures compel us to expand our traditional definitions for so many aesthetic situations that we currently encounter in the Information Age, perhaps it’s time to redefine what we actually mean when we use the nebulous word footage. At its essential core as an embodied meaning, footage too is basically information. All the footage that has ever existed, and ever will exist, is now at our command, and there’s considerable freedom in that situation, as long we don’t become the servants of our own technics.

From the cave wall to the computer screen in the blink of a hungry eye, images are inherently just visual data, and they are never permanent or unchangeable: like everything else around and inside us, they are eminently mutable. But so are the technics we use to transmit them. We’ve all been running hard to creatively catch up for a century or so. Yet sometimes it can feel like a hamster wheel, one first made of celluloid and now made of numerals. The human appetite for watching threatens to outdistance our own passionate desire for images in the first place.

When a new datum is formed by which other future operations can be carried out, everything before it is altered almost as much as everything after it. Artists can now approach the entire history of film as what it really is: a visual archive open to their own private research, play, and exploration in the form of critical commentary. From paint to film to pixels, the chance encounter of new media with old is a persistent continuum throughout the vivid kingdom of images.

But what happens when the evolution of our delivery systems continues to evolve past us, as it clearly must, and film language begins to compete with the next iteration of image play? A cybernetic feedback loop that people refer to, perhaps erroneously, as artificial intelligence looms in plain sight. What is the fate of found footage in the epoch we are now dreaming that we live in? What if one-day footage, as we historically recognize it, no longer exists? Are we already living in a hologram?

Artists can now approach the entire history of film as what it really is: a visual archive open to their own private research, play, and exploration in the form of critical commentary

Tougas recently reassured me that even if footage ceased to exist, then still there would always be artifacts. I feel better already, especially since his creatively hopeful attitude might actually suggest that the archival prompt machine known as AI could inherently be an exotic form of found footage. This makes sense, of course, coming from an artist whose own found footage-based works have broadly pursued the inherent nature of the film medium and the poetics of image, sound, and time.

Eventually, Tougas suggested to me that even the neural-netight be considered an evolving form of footage, albeit one with immaterial material. Tougas’ optimistic attitude resonates deeply for me:

The important word is not footage, but the word found. What’s interesting about found footage is the artist’s interaction with the unknown (Tougas, 2025).

So, anything that can be found in any medium, no matter how immaterial, and reconfigured via replication, might still be considered footage?

I think there will be found footage long into the foreseeable future. A USB or SSD drive, a hard-drive, a VHS tape, a floppy disk, a data warehouse, any old artifact will do. The challenge is the transition from analog representation to coded data that requires complex decoding technology for the representation to even emerge. We’ve been successful at preserving and reading visuals at least since the petroglyphs and cave drawings, all the way through painting and photography. But it’s the encoding and decoding process that changes the game: we’ve created a technology to suck all the images of the planet into one big vault where visual history can be accessed and mashed together in a storage facility so vast and yet so fragile because it depends on electricity: The Cloud. But it’s really just as vulnerable as famously destroyed libraries like Alexandria’s. We may also be quite disappointed in future found mash-ups because they only create by looking into a rear-view mirror (Tougas, 2025).

This cautious proviso raises concerns similar to those first expressed by the prescient German culture critic Walter Benjamin, especially in his visionary essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.’ Benjamin’s seminal notion of the aura of works of art and the potential decay they undergo via their technical reproducibility definitely needs our reassessment today, as an emblematic echo. Film itself, as potentially sentient, resists the extinction of found footage even if the future film archive moves beyond physical footage.

This notion of sentience embodies Benjamin’s concept of the optical unconscious while also suggesting why the future of found footage is still secure. It’s almost as if we don’t make films so much as films make us. So it’s all a matter of expanding our definition of what constitutes footage, and how any material or immaterial process may qualify for that designation. The entire history of film itself has its own embodied montage, allowing us to move freely in its memory-vaults whether or not any footage survives our rapid techno-advances. Montage, even the quantum kind that reconfigures footage as numerical information, is still at the beating heart of the experimental enterprise we call found footage, however we choose to define it.

Concerns about where our techno-fetishes might be leading, and what the future might look and feel like, are also top of mind for another film artist with a penchant for found footage I consulted, Richard Kerr. Kerr is a Canadian visual artist known for his expansive body of work, which has explored a multiplicity of genres and media since the 1970s. He has created over thirty films and videos that have been screened and collected around the world and is a professor of experimental film at Concordia University in Montreal. At times, my recent exchange with him seemed to share a subtle but tangible dread about a future which might already be here:

I always resisted putting my imagination on a credit card, and as far as digital versus celluloid and its nostalgia, digital came into my life principally because I am a practicing studio teacher and had to learn and understand it as a professional responsibility to my students. Otherwise I had no real interest in the process or its material quality, but I did find a way it could work for me though: converting analog material to digital files, which I consider hybrid media [that] is very different from pure digital. I am still permanently addicted to found materials, [they’re] it’s all I ever need, the ideas come from the material itself, and I also like the economy of re-cycling, or as it is now called up-cycling (Kerr, 2025).

Kerr also admitted to feeling nervous about perpetually newer tech waves overriding our creative parameters:

At a personal level, by the time digital came into my life, I was rather wary of yet more machines and more technology, it was a game that I was not prepared to play intellectually or financially. Also, digital always had a boogeyman quality for me, linked to corporate and institutional mandates. To be candid, though I cannot prove it, digital [technologies] messed up and confused quite a few generations of fine arts students. In the end, I am not overly taken by any media or technology that has an off switch. As far as celluloid nostalgia and experimental cinema go, maybe we have hit the moreness threshold, causing a collapse after sensory overload. I wonder what more can be done and what more needs to be done? At my senior age, the future is not of much interest, and as an artist, with AI coming directly at us, in its most basic sense that technology holds no intrigue for me because it can be anything. If you can imagine it, the machine will make it for you. That’s not a lot of fun for an artist. So thank the gods that the future comes with an on /off switch (Kerr, 2025).

But does the future really have an on/off switch, or have we just been convinced that everything is in our hands via freedom of choice and a vast menu of options? Meanwhile Tougas, who comes from the same seminal experimental generation as Kerr, readily concurs with any and all trepidation.

The issue of simulation vs. simulacra reveals a deep psychological panic: how do we exist in a world where we no longer know what is real? So now we have a mirror-like machine that has absorbed our entire human history and recycles it back to us at our command. Yet, for many the results aren’t quite satisfying, recalling Walter Benjamin’s lack of an original begetting a loss of aura in the mechanical (now numeric) age. Data-mined footage extends the reach of the found to the Internet 2.0, making preconceived or conceptual audio/video collage available to the artist. Ironically our comfortable acceptance of simulation prepares us for a total simulation, simulacra being the pejorative description of this totality. Generative AI is the outcome of data mining with typed or spoken prompts as the interactive interface between artist and machine. It’s pejorative because deep in our wetware we sense that something is lost: the aura of the authentic (Tougas, 2025).

Likewise, Harry Killas, a Vancouver-based documentary filmmaker and associate professor at Emily Carr University of Art + Design, exhibits a penchant for the authentic nature of analog found footage. In a distinctive parallel to artists using found footage for experimental aesthetic purposes, Killas has an intimate relationship with the found nature of archival materials, but one grounded in a historical perspective focused on producing authentic cultural documents.

His perspective, however, does acknowledge both the technical advances available to filmmakers like himself and the dangers of losing artistic control over the material process in the looming shadow of automation.

For Killas, the allure and appeal of working with found footage has a similar emotional content as the analog source original from which it is culled, but he is concerned with maintaining the veracity and fidelity of the original to ensure that history itself survives:

I love the hunt. The joy of finding reels of source footage drowsing intact in flea markets. There is great value in film discards, especially to someone like myself who works in the realm of historical research in the production of so-called straight documentaries (Killas 2025).

Killas has a high degree of reverence for these used outs, since they often flesh out the tapestry of the story he’s telling. In his case the motive is not to tamper with this footage but to operate in three key realms: conservation, preservation, and access. His key interest is in personalized documentaries critiquing social and political realities, much in the manner of the original found footage works by Soviet visionary Esfir Shub. Killas characterizes his keynote feature as that of transforming reality, not by an aesthetic of alteration but by preserving it—aka save, fix, and share:

My appreciation for found footage is embedded in the fact that I love old movies. If you’re interested in film it’s hard to avoid found footage, and any film is actually found footage. Today, it’s not a question of either/or film or digital, it’s more like both/and. Even though support for obsolete technologies is diminishing, digitizing analog material is crucial to preserve the content itself. And while we still use archaic analog terms like footage and cut (with no measurement or scissors), footage still exists in digital editing as content and information, as the cutting copy. But it’s now in the form of insertion in a digital timeline, with an indestructible format via an instruction file made as commands to a computer. Analog was linear, whereas digital is non-linear, and with film there are actual light particles reflecting back onto our optic nerves from the screen, [and] it’s warmer, but with digital, all the information sits somewhat coldly on the screen’s nerves. But despite these evolutions, and the newer ones still to come, film is not only not extinct, it still persists in the hands of artists who make their own strip reels, often out of exotic materials (Killas, 2025).

Like many other visual artists working with film, even those who embrace the extra control of digital editing options, Killas also experiences a sad expectation, a regret for something that might be lost in the advent of AI enhancements:

Though there’s much more information on the screen, often even beautiful information, we can also feel an absence: the missing aura of authentic images (Killas, 2025).

That wistful aura, championed so long ago by Benjamin and others, is essentially an emotional distance that does not decrease no matter how close we get to a great image—a Claude Monet, for instance. The corollary is felt at the other extremity, what Benjamin called the expressionless, a creative visual limit beyond which nothing more can be manifested or ascertained.

And that’s where Harry Killas left me with the most chilling example of the dangers of AI, when he shared with me his personal Monet story. As we know, Monet’s Impressionist painting style seemed to echo in advance the pixilated world of today. Increasingly abstract, his work also evolved along with his diminishing eyesight. Killas shared with me his visit to a Monet museum in Paris and his astonishment at seeing a painting ostensibly depicting a bridge over a river. But he was stunned by this painting, one that was almost complete abstract, as he could see no evidence of an actual bridge.

He took a photograph of it on his iPhone, and he held it up for me to see the alarming results. The AI program had auto-corrected the actual visual content Monet painted, rendering it as a more realistic looking bridge, one that was supposedly more accurate in cybernetic terms but far less compelling aesthetically. This was, I surmised, not only because it was missing the aura of the painting itself; it was also missing the Monet of Monet. The emotive warmth, the haptic charm, the experimental optics, the humanity in fact, were all spookily absent. It mindlessly fixed the Monet without being asked to.

In its own unique way, encountering a Monet in a museum is already a profound kind of found footage. And most of us might tend to agree that we prefer our Monet straight, no ice, no chaser, no AI. The same goes for our favorite films. The big question remains: what is the next seductively recursive technology coming around the bend to drive us forever forward, maybe to a receding destination at which we will never really arrive? What techniques and applications will we compulsively add to our ever-expanding lost and found department? Footage, more properly perceived now as information, whether it borrows from the past or the future, is still our elegant shared passion. Considering our ongoing appetite for footage itself, both original and found, analog or digital, the irony of protecting ourselves from the future raises an intriguing paradox: more importantly perhaps, just where is the future’s on/off switch?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Benjamin, Walter (1968) [1935]. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction / Illuminations, Sec.13. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Burroughs, William (1964). Nova Express. New York: Grove Press. P. 209.

Kerr, Richard (2025). Interview with the author, January, 2025.

Killas, Harry (2025). Interview with the author, January, 2025.

Tougas, Kirk (2025). Interview with the author, January, 2025.