Sometimes I Identify as a Man, Sometimes a Woman | Ronnie & Natalie Pollock, with introduction by Daniel Barrow | 2024

Have you ever wondered about the entanglements of Lauren Bugelsteeen—the first cousin of Lexi Bugelsteeen, the daughter of Buddy Bugelsteeen, and the niece of Eddy Bugelsteeen—who is engaged to a lesbian named Big Mike, as observed through the gaze of elegant British announcer John Ruggles Patria? Well, you aren’t alone. This is precisely the subject of Winnipeg artists Ronnie and Natalie Pollock’s 2024 found footage video Sometimes I Identify as a Man, Sometimes a Woman—an artwork which exists both as a standalone video and as a chapter of the Pollocks’ film Gay Nights (2025).

For those living in Manitoba, this is just the sort of salacious, small-town gossip you might expect to hear drifting out of Winnipeg’s suburb of Tuxedo, filtered through the vivid imaginations of brother-and-sister sensation seekers “Nifty” Natalie and “Rockin’” Ronnie Pollock. For those who live outside the perimeter, let me provide a bit of background on the Pollocks. They are best known for their infamous 1980s VPW program The Pollock & Pollock Gossip Show,1 which would be immortalized decades later through Daniel Barrow’s curatorial/archival/expanded cinema project Winnipeg Babysitter—an artwork that explores the golden age of public access television in Winnipeg, Manitoba.2

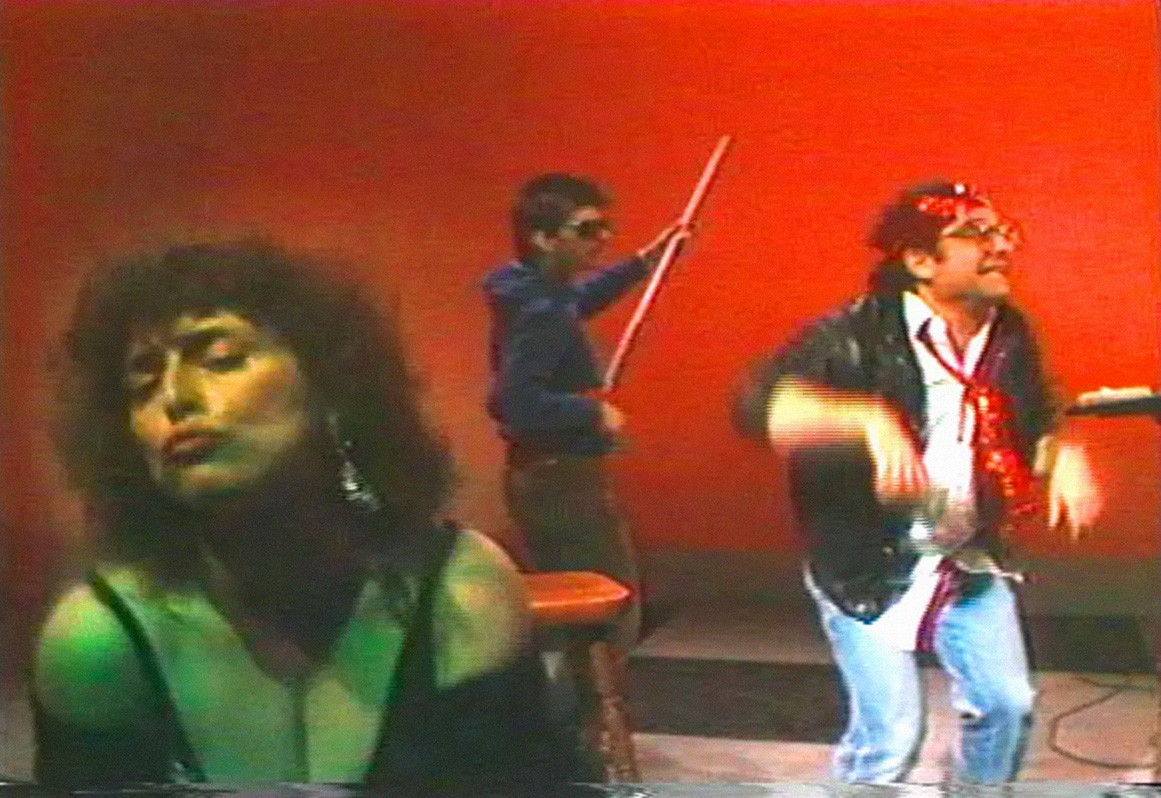

The Gossip Show was a DIY variety show hosted by the Pollocks who would invite ordinary citizens into the TV studio (often randomly recruited from shopping malls moments before their allotted time slot) in order to pry personal gossip from them. The interviews were punctuated by musical segments in which the Pollocks and friends would dance with abandon, scantily clad in signature garments: red sequin headbands, the “Red Shoes of Human Rights,” tinsel wigs, and a lot of cross-dressing. Their approach was surreal, gender-bending, sex-positive, and community-oriented. It was also philosophically and politically ahead of its time. Their motto—“Anyone can come and join us”—was sincere and radically inclusive, featuring a ragtag ensemble of people of all ages, abilities, and sexualities. Fan favourites included Paul, a cross-dressing Liberace impersonator; George Revine, an elderly, half-naked fan who proposed marriage to Natalie; and Kari and Nikki, two panic-struck high school students with towering 1980s coifs who became Winnipeg celebrities after their appearance on the show. The show itself is difficult to classify and exists somewhere between Dadaist performance art and exhibitionistic burlesque.

The show sparked both homophobic backlash and broader controversy, culminating in its cancellation—allegedly because the network objected to Natalie’s “bouncing breasts.” The Pollocks filed a discrimination complaint with the Human Rights Commission, which quickly caught the attention of international tabloid media and sensational daytime talk shows, leading to a level of public notoriety that few avant-garde figures can claim.

Self-taught, fiercely independent, and creatively inseparable, the Pollocks always made work on their own madcap terms and even had a few 1960s and 1970s Billboard hits.3 Now in their early eighties, the Pollocks have moved from VPW to YouTube, producing folk video art constrained only by open-source editing software and consumer-grade recording equipment. Their unorthodox practice exemplifies a form of impulsive artistic labor that is resourceful, unrestrained, and never contingent upon institutional validation.

Sometimes I Identify uses a queering strategy that has been described by Barrow as a “gender scramble”—the intentional mixing, remixing, and chaotic layering of gender stereotypes. The Pollocks’ characters don’t simply evade the traditional binaries of “male” or “female,” they jostle and swarm around the most exaggerated parodies of all genders. The video announces, “it doesn’t matter what gender we are assigned at birth, that practice is outdated. You should honour that and not question it.” As is common in the Pollocks’ work, the video walks a fine line between discomfort and humour—while not explicitly questioning this assertion, it attempts to understand and to come to terms with social constructions of gender identity. The title of the video itself argues that gender identity and sexuality are not only fluid, but also pretty funny. For example, when we are introduced to John Ruggles Patria, we learn that this is a story about how he rejected the gay lifestyle only to later embrace it due to his son, Susan Ruggles Patria (whom is, as the video informs us, “a wonderful young man”).

Since the 1960s the Pollocks have had a talent for courting attention and sensationalism. As such, Sometimes I Identify adopts a meme-inspired aesthetic conducive to viral circulation. The Pollocks’ works deliberately toy with click-bait conventions, employing provocative titles such as My Big Boner and Best Bum Videos and More! Many videos are structured by a quality of repetition—characteristic of Internet memes—and this informs the principal editing strategy for Sometimes I Identify. The perplexing narrative concerning the sexuality, love life, family lineage, and gender identify of Lauren Bugelsteeen and Susan Ruggles Patria recurs throughout the video, gradually transforming confusion into familiarity. By the end, these figures have been “meme-ified,” cemented in the viewer’s memory as their absurdities have become internalized through repetition.

Extending this notion of self-aware spectacle, the Pollocks deploy a recurring motif whenever the audience’s attention is under threat: the sudden appearance of the topless “Dancing Boy” who is heralded by the AI-generated voice of narrator John Ruggles Patria declaring, “Go, Dancing Boy, your moves are so delicious,” and the insertion of the notorious Basic Instinct (Paul Verhoeven, 1992) scene in which Sharon Stone, as we are informed by the narrator, “talks sexy and promotes her famous, wild vagina.” This intervention functions both as comic relief and as meta-commentary on audience desire revealing the Pollocks’ keen awareness of what advertisers and popular media have long exploited: the magnetic pull of sex appeal as a guarantor of attention.

The film’s soundtrack reinforces and amplifies its camp sensibility. It weaves together a eclectic mix of musical references—ranging from a kitsch rendition of Shirley Bassey’s “Diamonds Are Forever,” to an earnest/vulnerable and gender-bending performance of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s “Imagine,” to a wry linguistic study of the word action in Alicia Bridges’s queer disco anthem “I Love the Nightlife” (the way action is pronounced ak·syon is similar to the gag of the repeated I sound in I Identify).

Each selection oscillates between parody and sincerity, layering the film’s ironic humour with moments of genuine emotional resonance. This sonic collage performs what might be called a camp ethics of excess: indulging in overstatement and theatricality while simultaneously using these qualities to expose the artifice of emotional expression itself. By pairing songs so steeped in queer culture, Sometimes I Identify positions itself within a lineage of queer media that mines pop culture not just for parody, but for identification and belonging. Similarly, the utopian sentimentality of “Imagine” rubs against the glamour of “Diamonds Are Forever,” producing a friction that feels both ridiculous and sincere in the terrain where camp thrives. Meanwhile, an appearance of Elton John’s “Blue” and Bridges’s disco song extend this affective play into a self-conscious gesture.

What begins as a tangled web of local gossip and gender turbulence gradually reveals itself as an ode to creative freedom—a refusal to conform to aesthetic, social, or gendered expectations. Through their unapologetically lo-fi methods and chaotic storytelling, Ronnie and Natalie Pollock continue to affirm that art need not emerge from institutions to possess glittering cultural power. At a time when so much experimental work has become formulaic, where even gestures of transgression feel rehearsed and predictable, the Pollocks’ eccentric and erratic voices feel vital and irrepressible. Their work reminds us that the most enduring forms of expression are those that refuse to be neatly categorized, forever shifting, shimmering, and, like gender identities themselves, gloriously unstable and weird.

Endnotes

- 1. VPW was a community-access television station in Winnipeg, Manitoba that run from 1971 until 2001, when it was purchased by SHAW Cable.

- 2. In constructing Natalie and Ronnie Pollock’s biography for this review, I make use of research that was conducted by Daniel Barrow for Winnipeg Babysitter, which is available on Blu-Ray from the Winnipeg Film Group.

- 3. Their song “Destruction of Dawn Street” was produced by Dionne Warwick and released on Capitol Records in 1969. Their 1974 self-produced song “You Foxy Thing, I Love You,” released under the name Ronnie & Natalie O’Hara, charted on Billboard, peaking at twenty-three. “When Johnny Gets the Blues” made number one in the Iowa charts, and more recently, Ronnie and Natalie’s 1972 gutter-glam single “6 Times” was reissued by the Canadian label Supreme Echo as a split with Stumpwater’s “Turn Me On Woman.”