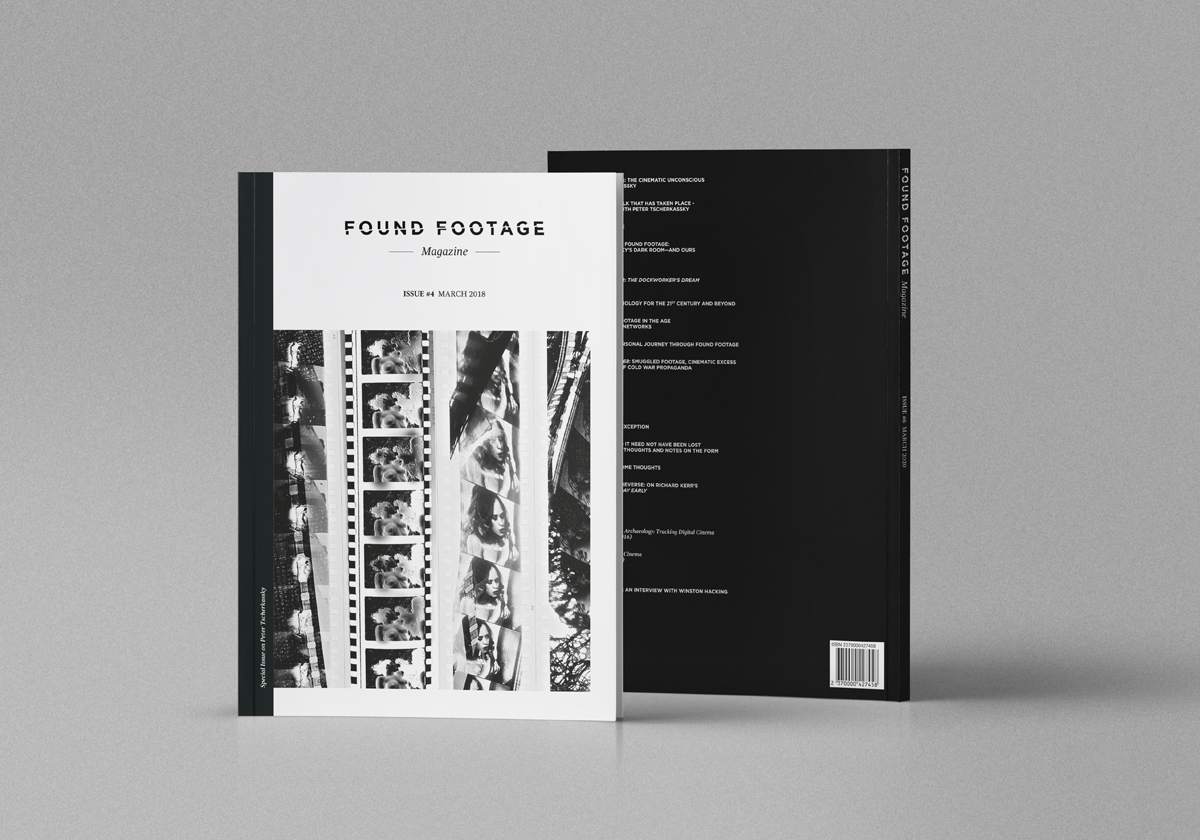

Issue #4

Special on Peter Tscherkassky

+ Other contents

- March 2018

- ISSN: 2462-2885

- Full-color magazine

- English

Controlled Chaos: The Cinematic Unconscious of Peter Tscherkassky, by Matthew Levine

On the surface, the films of Peter Tscherkassky seem to align with the guiding principle of most experimental cinema (especially that which employs found footage). In Tscherkassky’s words, that guiding principle is “to diminish the distance between the viewer and what is being viewed, to create a cinema that can be experienced as a physical experience, and to provoke a kind of active seeing”. While this broad description might be applied to a wide range of avant-garde modes, from the Dadaist films of the silent era to the most recent mixed-media installations, it underscores a formalist approach that seeks to strip the cinematic process of its homogenizing forces (narrative, character, representation) until all that’s left is the bare, beating heart of the moving image.

This is the realm of the abstract, or so it seems: a world where legibility and meaning matter less than sensorial impact and theoretical subtext. Indeed, while Tscherkassky’s approach undergoes significant changes throughout his career, what remains consistent is the foregrounding of the cinematic apparatus and the raw materials with which it works its illusionist magic. From the crude, punkish energy of Aderlaß (1981) to the libidinous dreamscape of The Exquisite Corpus (2015), there’s no escaping the immediacy of cinema as a tactile and sensuous object.

The Trace of a Walk That Has Taken Place – a Conversation with Peter Tscherkassky, by Alejandro Bachmann

Aroma for the Eye, by Virgil Widrich

Lost Material and Found Footage: Peter Tscherkassky’s Dark Room—and Ours, by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Essays

- A Sudden Passion 2: The Dockworker’s Dream by Bill Morrison, by Scott MacDonald

Like nearly all Bill Morrison’s work, The Dockworker’s Dream (2016) is constructed entirely from archival footage—specifically material collected at Cinemateca Portuguesa. As a filmmaker, Morrison is akin to Orpheus: he retrieves decaying footage from archives and brings it back to cinematic life, albeit transformed into a new form. Morrison has used the idea of dreaming as a way of working with archival footage (and emulsion decay) before, in The Mesmerist (2003) for example; and the idea of a fantasy voyage has been around from the earliest decades of cinema—think of Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon (1903) and The Impossible Voyage (1904). Morrison’s approach to the dream narrative in The Dockworker’s Dream, however, as well as in The Mesmerist and in other films, is to construct the dreams so that they simultaneously create a surreal story and provide a reflection on Morrison’s own filmmaking process.

- Remixology: An Axiology for the 21st Century and Beyond, by David J. Gunkel

What is original and what is derived? How can we sort out and make sense of questions concerning origination and derivation in situations where one thing is appropriated, reused, and repurposed for something else? What theory of moral and aesthetic value can accommodate and explain these situations where authorship, authority, and origination are already distributed across a network of derivations, borrowings, and re-appropriated found objects?

The following develops a response to these questions, and it does so in three steps or movements. The first briefly introduces the concept of remix and the opportunities and challenges that this now widespread content creation practice presents to existing models and theories of moral and aesthetic value. The second outlines the three elements of what I call remixology—a new axiology (or theory of moral and aesthetic value) that is designed to scale to these new opportunities and challenges. The third and final movement investigates the consequences of this proposal, demonstrating how remixology can be read backwards through time, providing us with some new perspectives on artistry and creativity in all human endeavors, and read forwards into the emerging challenges that have been made available by innovations in algorithmic content generation and computational creativity.

- Remixing Found Footage in the Age of Mass-Oriented Networks, by Oli Sorenson

Rather than questioning the limits of authorship, remixing found and sampled footage offers an opportunity to reposition mass-oriented and propertied content in the hands of ad hoc participants within peer networks of viewer-makers. As Paolo Virno said about general intellect, the disposition to learn, the whims of memory and relations to self-reflexivity are inexhaustible faculties of the mind that execute contingent and unrepeatable actions, so as to manifest the agency of individual contributors. But we have also seen historically—with kitsch in Benjamin’s Arcades, propaganda in cinema, and indeed with corporate interests in web enabled platforms—that this collective re-appropriation of creative abilities will not automatically guarantee a return to fair and inclusive socio-economic conditions, or safeguard the democratic principles of net neutrality. The activation of such political change still requires a sustained political struggle from the multitudinous users of networks, and constituents of nations, to herald distributed forms of authorship not as a source of economic problems but the solution to our current crises of representation.

- Lost Objects: A Personal Journey Through Found Footage, by Yann Beauvais

Since the late 1970s, the use of found footage has imposed itself as one of the most fecund fields of moving image production, both as film and video art. The use of fragments of found sequences is varied and expressed through a series of acts ranging from transfer to pure and simple appropriation, by way of diversion, quoting, and partial or total transformation of found objects. Reference to found footage implies considering not only an object—a fragment of film or video—but also a set of practices designating a genre, stretching beyond the aesthetic choices specific to each work.

- Czechoslovakia 1968: Smuggled Footage, Cinematic Excess and the Politics of Cold War Propaganda, by Gracia Ramírez

Czechoslovakia 1968 presents an interesting case of mixing propaganda’s claims of truth and political agitation together with the more knowingly rhetorical stances of found footage films. It uses archival materials as well as smuggled footage, engaging with the excessive and self-reflexive aesthetics typical of experimental cinema, such as the slide projector sequence that opens the film. It treads an ambivalent path which, on the one hand, invokes the evidentiary power of photographic and cinematic images for its propaganda purposes and, on the other, counters that impulse by calling attention to the film’s very mechanisms of construction of meaning. This approach effectively detaches spectators and results in what Michael Zryd identifies as the metahistorical form of found footage films, one that comments “on the cultural discourses and narrative patterns behind history”. The following analysis of the film and its context of production provides the opportunity to examine the uses and reception of a contentious propaganda film and to think about the received versions of what happened in Czechoslovakia now that the 50 year anniversary of the events comes close.

ARTICLES & INTERVIEWS

- The Rule and the Exception, by Mike Hoolboom

- For It to Be Found It Need Not Have Been Lost in the First Place: Thoughts and Notes on the Form, by Julie Murray

- Found Footage: Some Thoughts, by Malcolm Le Grice

- A Hummingbird in Reverse: On Richard Kerr’s Morning…Came a Day Early, by Stephen Broomer

Book Reviews

· Film History as Media Archaeology: Tracking Digital Cinema, by Eszter Polonyi

· Joseph Cornell Versus Cinema, by César Ustarroz

EXPLODING VISIONS, by Clint Enns

An interview with Winston Hacking

Démontage: Home Movie, by Cécile Fontaine

Artworks

by Félix Dufour-Laperrière & Dominic Etienne Simard, Michael Fleming, Cécile Fontaine, Michael Higgins, Josh Lewis, Pablo Marín, Sam Spreckley and Peter Tscherkassky.