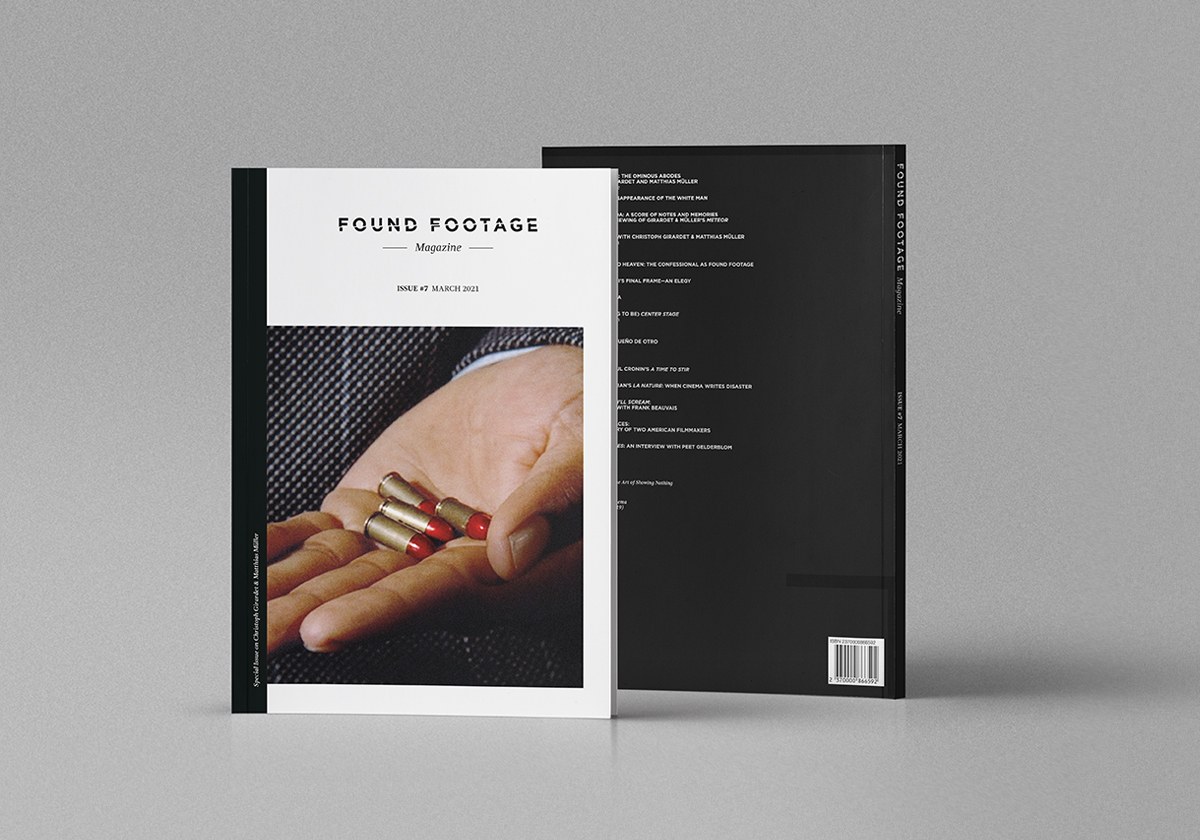

Issue #7

Special on Christoph Girardet & Matthias Müller

+ Other contents

- March 2021

- ISSN: 2462-2885

- Full-color magazine

- English

A Haunted House: The ominous abodes of Christoph Girardet and Matthias Müller, by Matthew Cole Levine

Their approaches to found footage, at once likeminded and singular, have served Christoph Girardet and Matthias Müller well since 1999, during which time the two of them have collaborated on nearly thirty films and photographic works. Varied metaphors and modes of inquiry have been used to analyze their oeuvre: to some, Girardet and Müller provide a “suggestive continuum,” exposing the patterns of light and darkness, absence and presence, by which cinema operates; to others, the filmmakers dissect the body of film history and of the cinematic apparatus, suggesting the moving image as a corporeal grouping of skin, guts, brains, and bones to pick apart. Still others see their work as “poignant commentar[ies] on longing, space and mystery” or as dreamlike excavations of cinematic mythology. They’re all correct, but to me, what sets Girardet and Müller apart—what elevates their work from formalism to radical humanism—is the central metaphor of the house as a site of horror and desire, an analogue for cinematic apparatus itself, and a refraction of the political ideologies lying at the heart of late capitalism, as filtered through the visceral joys of the moving image. Through their films, Girardet and Müller invite us into the haunted house of cinema, which burrows its way into our brains like a possessing spirit, violence masquerading as pleasure.

Personne : The disappearance of the white man, by Catherine Russell

Fenestra Rotunda: A score of notes and memories following the viewing of Girardet & Müller’s Meteor, by Stefano Miraglia

A Conversation with Christoph Girardet & Matthias Müller, by Alejandro Bachmann

Essays

- Hitching a Ride to Heaven: The confessional as found footage, by Clint Enns

Given the proliferation of online confessional videos, it should come as no surprise that artists have appropriated them and incorporated them into their own artworks. The confessional video is often emotional and candid, a raw glimpse into the emotional turmoil and struggles of others. Given the nature of the confessional—an individual’s private reflections on their struggles, thoughts, actions, and behaviours that are considered shameful or disgraceful—it is a mode ripe for interrogation and hermeneutic readings. The confessional is a way in which the confessor acknowledges and recognizes deviations from accepted societal norms and values; therefore, by analyzing the confessional it is possible to unpack the underlying economic, political or ideological conditions that ultimately led one to confess. Through appropriation, the raw underlying emotions of the confessional can be used by artists to construct new narratives and sensations. In this essay, I provide a brief historical overview of the confessional focusing on its social and political functions. I discuss artistic uses of the confessional mode, and the relationship to its contemporary form, the online confessional video.

- Abbas Kiarostami’s Final Frame—an elegy, by Scott MacDonald

While “24 Frames” is, of course, a reference to celluloid filmmaking, 24 Frames is, among other things, Kiarostami’s revisiting and recycling of his photography, particularly his black and white photography of the Iranian countryside in winter. 24 Frames opens with a manipulation of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting Hunters in the Snow (Winter), simultaneously an homage to Bruegel and a demonstration of what Kiarostami means to do with his own photographic work in the following 23 Frames. Subtle additions to the painting—smoke coming from chimneys, birds flying, a dog entering the image, three cows…all accompanied by faux environmental sounds—make clear that Kiarostami was exploring a range of possibilities that working in digital made available to him. He then revisits his own photographs, providing manipulations—sometimes subtle, sometimes obvious—of each.

- Retracted Cinema, by Peter Freund

The concept and practice of retracted cinema pose a polemical contrast with the expansionist, annexational logic of expanded cinema by means of a process of folding found or archival footage back on itself in the manner of a conceptual origami. The algorithm as such is radically abstract (and abstractable) and demonstrates that execution and application turn out to be a distinguishable instance of conception and instruction. In short, the algorithm itself is already taken out of context to the same extent that any readymade is. It is this potentiality at the root of the algorithmic—whether constructed with film/video editorial tools or with coding—that the work of retracted cinema seeks to foreground, exploit, and even celebrate. This essay introduces a theoretical framework for appreciating this practice’s use of algorithmic procedures performed on appropriated film materials in advancing a politics and aesthetics of the non-orientable surface.

- Being (or Seeming to Be) Center Stage, by Jonathan Rosenbaum

What does it mean to be, as Stanley Kwan’s title has it, Center Stage? Insofar as it’s possible to deal with the present moment—that is to say, the present pandemic moment—historically, I think that one of the most dubious and objectionable words repeatedly intoned with gravity by TV news commentators is in fact the word historic. Given an extra spin in some cases by American exceptionalism, even during a period when our former President Donald Trump has opted out of many of our accords and treaties, it is used smugly and even narcissistically yet also quite vaguely to describe us and our current experience, as if to distinguish both as being somehow superior to or on a higher plane than those who preceded us or those who will come afterwards—our supposedly ahistoric (and therefore less important) grandparents and grandchildren and what they had or will have to deal with. This is arguably little more than a futile effort to legitimize and glamorize our inertia and helplessness by asserting that the mere fact that we’re alive during an awful period automatically makes us historic or historical. Simply put, it’s our mute, passive suffering that allegedly brings significance to our troubled times, not our existential decisions.

ARTICLES & INTERVIEWS

- More Is More: Paul Cronin’s A Time to Stir, by Scott Macdonald

- Artavazd Pelechian’s La Nature : When cinema writes disaster, by Anna Doyle

- Just Don’t Think I’ll Scream : A conversation with Frank Beauvais, by Nazaré Soares

- Secrets as Surfaces : Prayers in memory of two American filmmakers, by Pablo Marín

- When Forever Dies : An interview with Peet Gelderblom, by Joshua Wille

Book Reviews

· Absence in Cinema: The art of showing nothing, by César Ustarroz

· Film and Art After Cinema, by César Ustarroz

DÉMONTAGE: ATRAPADO EN EL SUEÑO DE OTRO, by Ernesto Baca

Artworks

by John Baldessari, Lola Dupre, Jean-Jacques Martinod, Audrey Jeamart, Miriam Tölke, Bill Noir, Monique Vettraino.