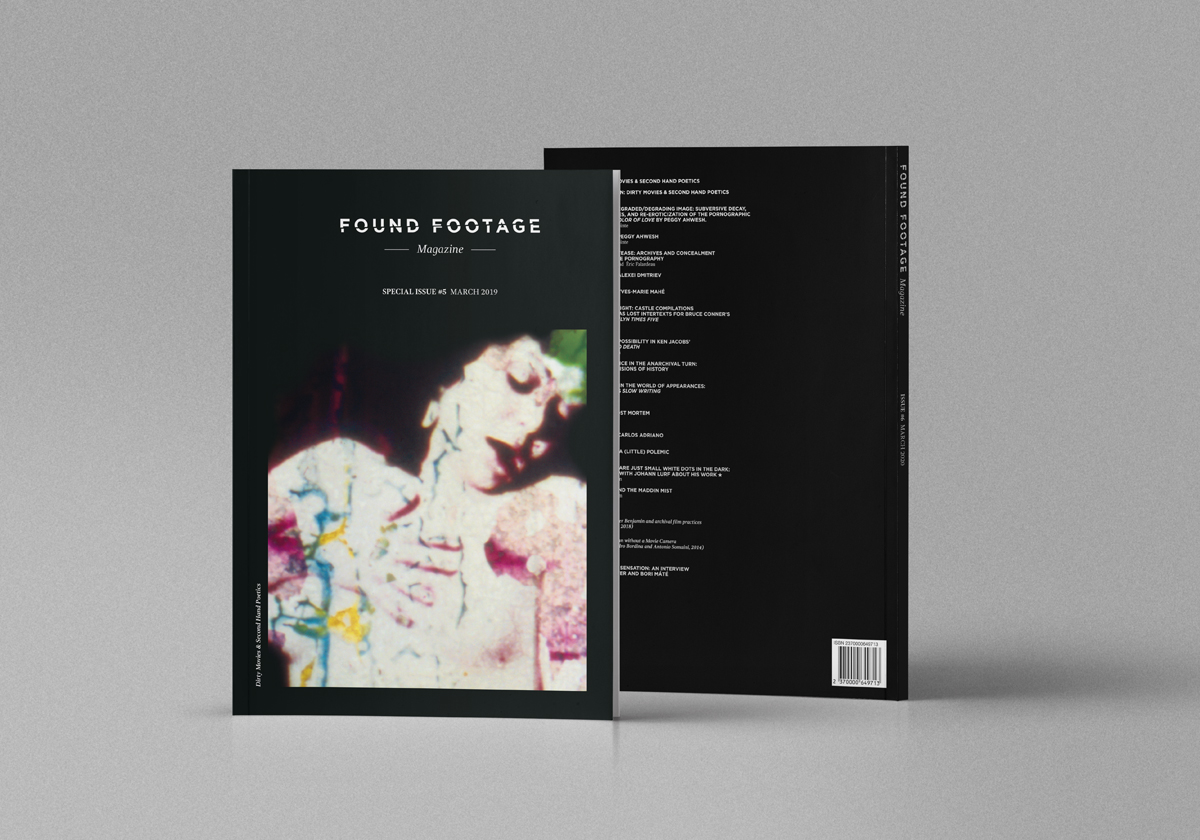

Special Issue #5

Dirty Movies & Second Hand Poetics

- March 2019

- ISSN: 2462-2885

- Full-color magazine

- English

(In)appropriation: Dirty Movies and Second Hand Poetics, by André Habib

Can found footage filmmaking inform an archaeology of pornography that would account for the institutional, material, technological and social dimensions that are part of the very archive of pornography? This question is in fact part of a more general thinking of found footage filmmaking as a way to discuss and better understand the history of film heritage and technology, inside and outside of archives proper. By asking simple questions like, “How is found footage actually found and appropriated?”, the idea is to convey what found footage films tell us about archival access, film technology and materiality. Can found footage films give us a sense of what was and is today considered worthy of preserving or, on the contrary, considered disposable at a given historical time? Can these filmmakers shed new light on the archive, simply by displacing or misplacing films that are often dismissed because they were useful (educational, industrial, training films, pornography, advertisements) and have become useless (that is, useless for some but insightful, beautiful, disturbingly poetic for others)? I think these questions can offer a contribution to contemporary debates in the field of moving image archives, at the cross-point between history, technology and film aesthetics. And I would argue that this is particularly true of the exquisite corpus this dossier on pornography and found footage films wishes to highlight.

Dossier Essays

- Revisiting the Degraded/Degrading Image: Subversive Decay, Parallel Legacies, and Re-Eroticization of the Pornographic Archive in The Color of Love by Peggy Ahwesh, by Alice Michaud-Lapointe

Intense, blood-soaked, feminist, political, organic, avant-garde, cinephilic: those are all terms that can be used to describe Margaret—known as ‘Peggy’—Ahwesh’s The Color of Love (1994, 16 mm), which happens to be a pornographic film found in one of Bard College’s rubbish bins. Ahwesh’s gaze and touch turned this junk reel into a nine-minute experimental film. Since her debut in the 1980s, Ahwesh has played a very important role in the field of experimental cinema, and her influence has also been strong in the worlds of video art, contemporary art and women’s cinema. Her work, which spans four decades and encompasses an impressive variety of practices through different formats (Super 8, PixelVision, digital video, literary adaptations, documentary, bricolage, home movie), has often been characterized by its heterogeneity and taste for formal radicalism.

- To Strip and to Tease: Archives and Concealment in Found Footage Pornography, by Annaëlle Winand and Éric Falardeau

Pornography has a specific place in experimental found footage filmmaking. Not only are its pleasurable images used as commentaries ranging from social critique to outright humor or as an aesthetic exercise, but also because porn’s body of work constitutes an extensive resource for filmmakers to dig from. Crisscrossing medium, aesthetic style and types of production, the genre has been constantly diversifying itself. More recently, porn images, both amateur and mainstream, have been multiplying through new technologies and online platforms. As a raw filmic and videographic material, it is therefore a fertile ground, allowing multiple stories to be told. What interests us here is precisely this extensive body of work, often called the porn archives, and its translation into found footage filmmakers’ works.

- Hidden in Plain Sight: Castle compilations and nudie films as lost intertexts for Bruce Conner’s A MOVIE and MARILYN TIMES FIVE, by Louis Pelletier

Bruce Conner’s A MOVIE (1958) can lay claim to being one of the most widely seen experimental films in history. Interestingly, it is also largely made up of moving images scavenged from prints of some of the most widely disseminated films in the history of photochemical cinema. Yet, very little attention has to this day been granted to the tension between the familiar nature of the images repurposed by Conner and the unsettling oddity of A MOVIE. This situation appears to be a consequence of a significant gap in cinema scholarship regarding small-gauge cinema, and more particularly the production of commercial films primarily intended for exhibition in the home.

This essay will seek to demonstrate that a greater awareness of the original exhibition context, forgotten genres, and ubiquitous nature of the moving images recycled in the found footage films of Conner can lead us to a better understanding of the defamiliarization process at the core of the artist’s media critique. Close textual analysis of A MOVIE, as well as of some of the small-gauge films that have provided much of its content, will first permit me to argue that Conner’s intertextual play with his source material is much more significant than what previous studies have assumed. We will then examine how the artist’s engagement with repetition and the materiality of film in MARILYN TIMES FIVE (B. Conner, 1973) echoes various practices associated with the circulation and exhibition of small gauge pornographic films.

Dossier Interviews

- Interview with Peggy Ahwesh, by Alice Michaud-Lapointe

- Interview with Alexei Dmitriev, by André Habib

- Interview with Yves-Marie Mahé, by André Habib

ESSAYS

- Indictment and Possibility in Ken Jacobs’ Star Spangled to Death, by Zachariah Anderson

In Star Spangled to Death (1956-60/2003-04), Ken Jacobs tactically intervenes in found footage to indict the media’s ongoing allegiance to oppressive institutions. Jacobs’ aesthetic interventions expose the ways this alliance has been sustained through the cinema’s perpetuation of reductive historical narratives, while incriminating present spectators’ passive consumption of these simplified versions of the past. In response to this indictment, the film opens new space for spectators to explore possibilities of actively constructing their own meaning from historical documents. Specifically, Star Spangled to Death prefigures—or illustrates the imaginative possibility of a future shift toward—a re-functioning of today’s dominant mode of viewing: the consumption of digital video on personal screens.

- Aesthetic Violence in the Anarchival Turn: On the Infinite Visions of History, by Kamila Kuc

I consider aesthetic violence to be a politically necessary artistic action that aims to expose the workings of what cultural theorist Rob Nixon calls slow violence: violence that “occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all”. In this article, I examine three films: two features—Rey (Niles Atallah) and Spell Reel (Filipa César)—and my own short film, I Think You Should Come to America. Each combines archival footage with new material to portray instances of long-term violence.

Exploring aspects of colonisation and oppression, the archive in all three films provides a space to re-imagine painful histories that require new interpretations. Each film exemplifies what I refer to as anarchival turn—a response to the economic and political impact of neoliberalism with its destructive effects on alternative forms of culture production. In their radical ways of working with historical footage, these three films can be seen as alternative anarchival practices.

- There’s a Crack in the World of Appearances: Thom Andersen’s Slow Writing, by Matthew Levine

The films and writings of Thom Andersen might be said to subscribe to a similar kind of guardedly humanistic postmodernism. Straddling the worlds of film theory, history, and criticism, running the gamut from primitive silent cinema to the Hollywood mainstream to the avant-garde and everything in between, Andersen’s tastes are nothing if not eclectic. His essays, compiled in the anthology Slow Writing: Thom Andersen on Cinema (The Visible Press, 2017), range from pornography to Michael Moore, from The Crying Game (Neil Jordan, 1992) to Andy Warhol, from arthouse auteurs like Pedro Costa and the Dardenne brothers to overlooked trucker films from the 1970s. Lowbrow or highbrow, obscure or populist, from 2018 or the nineteenth century—these distinctions don’t matter to Andersen, a ravenous consumer of moving imagery. But his cinematic erudition is hardly self-satisfied; in all instances, Andersen explores the structures of genre, narrative, and aesthetic form to reflect upon a social and political reality in which representation matters and the stakes are high. “We are all so busy creating our own little stories,” Andersen writes, “that we miss the movements of history”. His aim is to bring these dialectical movements to the fore, ensuring that we can’t ignore the larger social and political forces mobilizing the media narratives and imagery that surround us.

ARTICLES & INTERVIEWS

- Interview with Carlos Adriano, by Scott MacDonald

- Found Footage: A (Little) Polemic, by Peter Gidal

- Constellations are just Small White Dots in the Dark: A Conversation with Johann Lurf about his Work ★, by Alejandro Bachmann

- The Green Fog and the Maddin Mist, by Jonathan Rosenbaum

BOOK REVIEWS

· Archiveology: Walter Benjamin and archival film practices, by César Ustarroz

· Paolo Gioli: The Man without a Movie Camera, by Matthew Levine

THE LOGISTICS OF SENSATION, by Dan Browne

An interview with Péter Lichter and Bori Máté

DÉMONTAGE. Self Portrait Post Mortem, by Louise Bourque

Collages

by John Stezaker, María Cañas, Guy Maddin, Mimmo Rotella, Matthieu Bourel, Douglas Gordon, Mariana Freijomil and Eli Craven.